Reggae blew up in the 70s and 80s because it introduced a new rhythm to the world.

This rhythm, built on the upbeats, reinvigorated the songwriting of many artists in many genres from pop to punk.

Although Bob Marley is the most famous Reggae artist, other artists like Jimmy Cliff, Sister Nancy, and Peter Tosh also had a big hand in making this genre more popular.

We’ll take a look at their songs as well as a few others to explore how you can learn from these great artists too.

Table of Contents

- Reggae Chord Progressions

- I – V – I – V – I – V – II – I – II – V – I – V

- i – VII – VI7 – v7 – iv7 – (VII – i)

- I – vi7 – IV – I

- i – i – iv – iv – i7 – i7 – i7 – i7

- (I – bVII)

- I – (IV – V) – I – (ii7 – V)

- I – bVII

- I – IV – I – I – I – IV – V – V

- I – V – IV – V – I – ii

- (I – I6) – (IV – III) – (IV – II6) – (I6/4 – V7) – (IV6/4 – I) – (I – V)

- What makes a reggae song?

- How to play reggae chords the right way?

- Should you use an acoustic or electric guitar when playing reggae?

Reggae Chord Progressions

I – V – I – V – I – V – II – I – II – V – I – V

Lots of chord progressions in Reggae, and many kinds of music, will last either 8 or 12 bars long.

Sometimes they’ll go as far as 16 or 24 but that’s usually more than many listeners can take in.

Like we said in the intro sections, lots of Reggae will use the I, IV, and V chords in some combination.

This progression however takes a little detour from that.

Instead of using the IV as much, it wants to use the major II chord. In G major, there would be an Am chord instead as its diatonic to the key. Diatonic means basically that its in key.

The note C#, the third of A major, is not diatonic or in the key of G major.

This is a very subtle way to add variety and spice to a progression in major using I, IV, and V chords.

There is absolutely no rule saying you must stick to the notes of the key of G major.

i – VII – VI7 – v7 – iv7 – (VII – i)

This next progression may not be the first song that comes to mind when you think of Reggae.

We’re about to get to Bob Marley though I swear!

I included this one because it has that very familiar Reggae rhythm but uses some other harmonies not typical of the genre, like the VI7 and iv7 chords.

You see this one is in a minor key, G minor:

- G minor scale: G – A – Bb – C – D – Eb – F

- Gm (i): G – Bb – D

- F6 (VII): F – A – C – D

- Ebmaj7 (VI): Eb – G – Bb – D

- Dm7 (v7): D – F – A – C

- Cm7 (iv7): C – Eb – G – Bb

Lots of Reggae won’t take full advantage of the minor key.

However, when you listen to the song, you’ll notice that it has the same rhythm.

To play in any genre, the chords are important, but the rhythm may be the most important part.

I – vi7 – IV – I

This Bob Marley song has a very simple chord progression. Just 4 bars long!

Lots of Reggae music has gospel roots to it, which is why you’ll see plenty of usage of the IV chord.

The IV chord is the focus of lots of Gospel because of the plagal cadence of I – IV that’s used so often.

Anytime you see a IV chord going back to the I, it can suggest this sound.

To understand this better, let’s break down the chords again:

- D major scale: D – E – F# – G – A – B – C#

- D (I): D – F# – A

- Bm7 (vi7): B – D – f#

- G (IV): G – B – D

All of these chords fit perfectly, and are diatonic, within D major.

You aren’t going to see a lot of chromaticism or diminished chords in the Reggae genre.

It’s all focused on bright sounding major chords for the most part like those two, as well as the minor chords within the major key.

i – i – iv – iv – i7 – i7 – i7 – i7

We covered the key of G minor just a few songs ago with “Roxanne” so hopefully you’ll see how this one works already.

It involves only two chords: the i (Gm or Gm7) and the iv (Cm).

Both harmonies will be used quite often together in Reggae and in some Blues music as well.

You can see it as a variation on the I – IV change we just talked about too, except with minor chords.

Remember that the structure of the chords will be different in a minor key.

The IV in major will be different in minor, and so on for each harmony.

This is important to remember as you navigate different harmonic systems like the harmonic minor, melodic minor, and chromaticism.

(I – bVII)

The I – bVII chord change is used quite often in many types of music as well.

The reason it sounds so appealing is because it sounds like it’s in a major key, but also sounds chromatic.

This is because in G major the F chord is not diatonic to G major.

These two chords appear together only in the key of C.

So you can see it as being a mixolydian progression in G mixolydian, or as a G major progression with a bVII chord.

- G Major Scale: G – A – B – C – D – E – F#

- G (I): G – B – D

- F (bVII): F – A – C

This is one of the simplest ways to add chromaticism to a progression.

The bVII chord is very useful because it comes from the parallel minor scale.

Taking chords like the iv, III, and VI and putting them into a G major progression are useful ways to shake up a Reggae progression.

It doesn’t have to be complicated to use ideas like chromaticism.

What is required is to let go of the idea that you must only use the notes available in the major scales you’ve been taught up until now.

I – (IV – V) – I – (ii7 – V)

One idea we have touched on a lot is that of harmonic rhythm.

This is where you decide how many harmonic changes will occur per bar.

The ear can only handle so much so 4 is the maximum I’d recommend, and 2 is the norm if you want to do more than 1 change per bar.

You can see this happening in this progression with the 2nd and 4th bars.

Choosing your chords and the order of them are just one aspect.

Another important aspect is this idea, harmonic rhythm.

If you start using this idea regularly, your songwriting will start to become more fresh.

As for the chord choices, once again it’s using the diatonic chords of B major, and in particular the I, IV, and V chords.

- B major scale: B – C# – D# – E – F# – G# – A#

- B (I): B – D# – F#

- E (IV): E – G# – B

- F# (V): F# – A# – C#

- C#m7 (ii7): C# – E – G# – B

I can see all of this because I’ve memorized the chords of all the key signatures.

It takes time to do this and there is no trick to memorizing it quickly.

The circle of fifths can help you understand it, but there’s still the task of memorization.

I recommend that you write down the I, IV, and Vs of each key and quiz yourself.

After that, do the iis, iiis, and vis.

Then quiz yourself on what notes are in each chord and scale.

This is how I’m able to write this info for you and recall it by memory.

It’s also how I’m better able to see the musical relationships I’m showing you in this article.

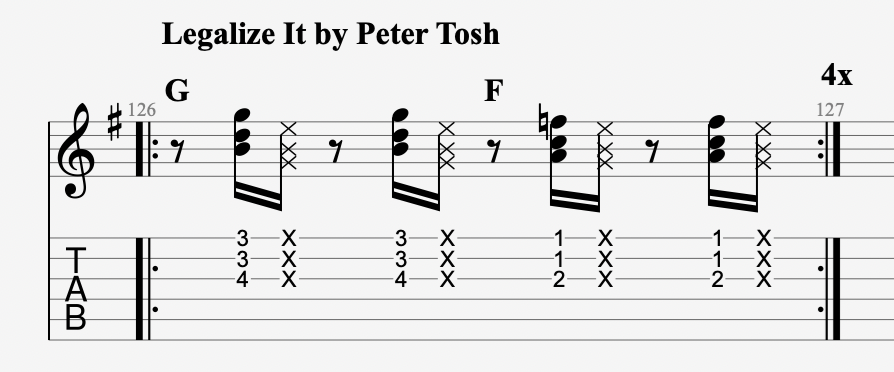

I – bVII

So you’ve already seen this change, the I – bVII, but I wanted to include this example because of the rhythm.

Also I included it because its a great song that’s not as well known as some of the others here.

The rhythm of reggae comes down to syncopation.

This is the method of accenting off beats like 2 and 4 in measure of 4/4.

It’s also when you play rhythms that are slightly off of those beats too.

You hear this idea all the time, and its a great way to make your riffs more musical if you’re stuck in straight 8th notes or 16ths.

In Reggae, the formula is to play quick 8th note up/down strokes on the 2 and 4.

Look at the riff above. It’s two quarter notes, then quick 8ths on the “ands” of 3 and 4.

Maybe you’ve heard of the way people break down rhythms in guitar playing.

For 8th notes, it’s 1-and-2-and-3-and-4-and. Count out the ands and the numbers and you get 8, for 8 notes in a bar of 4/4.

Hopefully you’re following this and have some background in reading rhythms.

The most important thing to understand is that reggae focuses mostly on the off beats.

I – IV – I – I – I – IV – V – V

A tendency that many beginner songwriters have is the need to change chords every single bar.

This is not at all necessary and one chord can easily last for several bars before another change is made.

This is often the standard for progressions that back verse melodies and lead guitar solos.

Think back to the concept of harmonic rhythm.

Just as you can plan how many changes per bar will occur you can also choose to restrain this aspect of making music.

In the progression above, the I is played for the 3rd to 5th bars. In the 5th bar, the progression kind of starts over but goes to the V chord instead for the last two bars.

It’s easy to dismiss the utility of I, IV, and V chords because of their simplicity.

If you just play D, G, and A together you’re not likely to have much difficulty as a guitarist.

However we’re not covering just guitar playing but theory and songwriting.

The goal of making music shouldn’t be to make the most difficult piece possible, but to engage your listener and elicit an emotional response from them.

I – V – IV – V – I – ii

This is another great example of how you can exploit and use the concept of harmonic rhythm.

It’s also a great example of the reggae rhythm mentioned earlier where we focus on the “ands” of each beat.

Learning and studying music helps you see a lot of these connections in various ways that you couldn’t before.

So good for you for going through all of these examples!

So the song here is using the I, IV, and V chords a little differently.

The verse just goes back from E to B (V) several times before a pre-chorus of A (IV) to B (V) shows up.

Finally, the song goes to a progression using the I and ii (F#m) chords.

(I – I6) – (IV – III) – (IV – II6) – (I6/4 – V7) – (IV6/4 – I) – (I – V)

The last progression we’re going to discuss is much more complex than the others.

So let’s breakdown the key and the chords once again:

- F major scale: F – G – A – Bb – C – D – E

- F (I): F – A – C

- F6 (I6): A – A – C – F

- Bb (IV): Bb – D – F

- A (III): A – C# – E (C# isn’t part of F major)

- G/B (II6): B – D – G – D (B isn’t part of F major)

- C7sus4 (V7): C – E – F – G – Bb

The other slash chords I haven’t included because they have the same notes as the other chords.

Slash chords however are a giant unexplored area of the guitar that has lots of potential to reinvigorate the chords you’re already playing.

So this progression uses slash chords, the I, the IV, and the V7 chord.

The harmonic rhythm has 2 changes per bar.

The major III chord (A) and G/B chord (II6) throw in some intervals that add some more depth to the common chords we’ve been using so far.

The C#/Db is a minor 6th interval in the context of the F major scale, while B is a #4 in F major.

These two intervals are often used in some way to add chromaticism to a major key progression.

This music theory is a little advanced but if you can simply see that those two notes are not part of the F major scale, then you’re much further ahead than many songwriters.

What makes a reggae song?

Like we mentioned before, a Reggae song’s primary musical characteristic is its rhythm.

This rhythm puts a lot of its focus on the upbeats, the 2s and 4s, of a song that’s in 4/4, in this way, the guitar acts like a snare drum does, accenting the offbeats/upbeats.

The other primary characteristic of Reggae songs is that they use lots of major key progressions; these progressions, like many other genres, use the I, IV, and V chords quite a bit.

Lastly, Reggae likes to use pieces of chords, and often on the G, B, and high E strings.

These chords are very bright sounding and can be strummed easily for those offbeats.

How to play reggae chords the right way?

To play reggae chords, you will need to understand the basics of chord structure and theory.

Start by familiarizing yourself with major, minor, and seventh chords.

Reggae is often based on a I-IV-V progression using these basic chord types.

When playing a reggae song, it’s important to focus on the offbeat and strum each chord with a light staccato pattern, this is what gives reggae its signature “chop”.

To sound more authentic, add some open string chords known as skanks to your playing.

These are usually played in between the I-IV-V progression and give a real reggae vibe to your song.

When playing skanks, strum down on each beat and mute the strings with your fretting hand.

This will give it a tight and percussive sound that is characteristic of reggae.

Finally, when playing reggae chords pay attention to the feel of your playing.

Reggae has a laid back, chill vibe that should be present in the music you make.

To accentuate the syncopated rhythms of reggae, try lifting your fingers off the fretboard after each chord is strummed.

This will create a choppy, percussive sound that helps to drive home the signature reggae feel.

Lastly, experiment with varying chord voicings and strumming patterns to find the perfect sound for each song.

Should you use an acoustic or electric guitar when playing reggae?

The answer to this question I think largely depends on your preference as a musician and what type of style you’re going for.

Many reggae songs are traditionally performed using acoustic guitars; however, electric guitars can be used too.

The warmth of an acoustic guitar is often preferred in reggae music because it creates a unique sound that is closely associated with the genre.

However, it’s worth noting that electric guitars offer more flexibility and sound control, such as the ability to use effects pedals and amplifiers for a fuller sound.

If you want an authentic reggae feel, an acoustic guitar is usually the way to go, but if you’re looking to experiment with more modern sounds, an electric guitar may be the better option.

No matter what you choose, both acoustic and electric guitars can add a unique flavor to your reggae music.

Loves studying classical piano, youtube video tabs, and music theory textbooks to get insights into guitar playing that no one else has uncovered yet. In his spare time, he can be found relaxing at the beach in San Diego, or adventuring somewhere around the world.