The A major guitar scale is an excellent way of grasping all of the fundamental and most crucial concepts of not only the guitar but also music in general.

Its key signature has three sharps, C#, and F#, and G#, its relative minor is F# minor, and its parallel minor is A minor.

The key of A major appears frequently in chamber music and other music for strings since these tend to favor sharp keys.

Chamber music is a form of classical music that is composed for small groups of instruments that could fit in a palace chamber or a large room.

Also, the triads in this key are A major, B minor, C# minor, D major, E major, F# minor, and G# diminished.

Two great examples of songs written in A major are “Chasing Cars” by Snow Patrol and “Tears in Heaven” by Eric Clapton.

Table of Contents

Notes In The A Major Scale

The A major scale, like most other scales, is made up of seven notes.

The notes in the A major scale are: A B C# D E F# G#

Changing one or two notes will change the key of the musical structure you’re working with, for example:

- If you change the D to D# and keep the rest of the notes of the A major scale, then you get the E major scale.

- If you change C# to C, F# to F, and G# to G, then you get the notes of A minor.

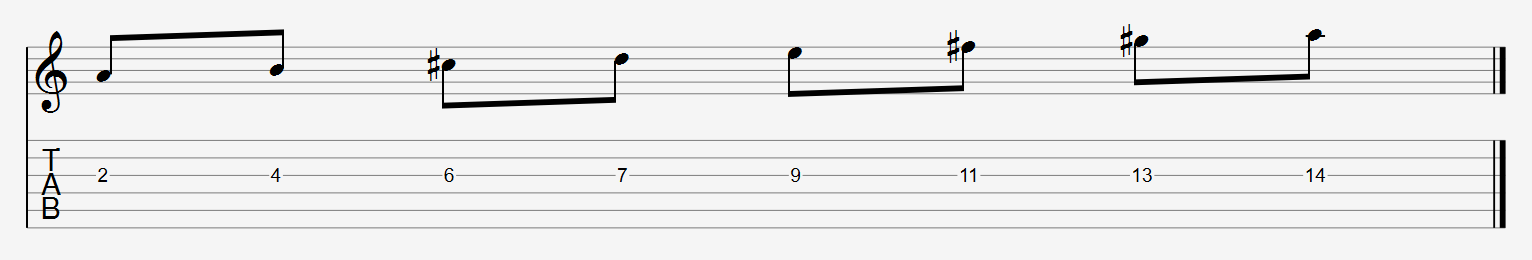

To easily play these notes in this exact order without alternating between your guitar strings, you can use your guitar’s 3rd string (G string) starting on fret 2:

If this is the first scale that you’re learning, this won’t make too much sense to you right now, but if you’ve learned other major scales before, you might be able to recognize something.

There is sort of a formula or sequence that these notes follow on your guitar fretboard, that is:

- A major Scale = A (W) B (W) C# (H) D (W) E (W) F# (W) G# (H)

Intervals Of The A major Scale

An interval in music is defined as a distance in pitch between any two notes.

Intervals are also named by size and quality, and they are many different ways that you can measure the intervals of a scale, for example, in half-steps, semitones, or frets.

The possible qualities are major, minor, perfect, diminished, and augmented.

The intervals of the A major scale are:

- Tonic: A

- Major 2nd: B

- Major 3rd: C#

- Perfect 4th: D

- Perfect 5th: E

- Major 6th: F#

- Major 7th: G#

- Perfect 8th: A

In the formula that we saw in the previous section, the parentheses were the distance between the notes of the major scale, which would essentially be:

whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half

For those who don’t know, “whole” refers to a whole tone, whereas “half” refers to one semitone.

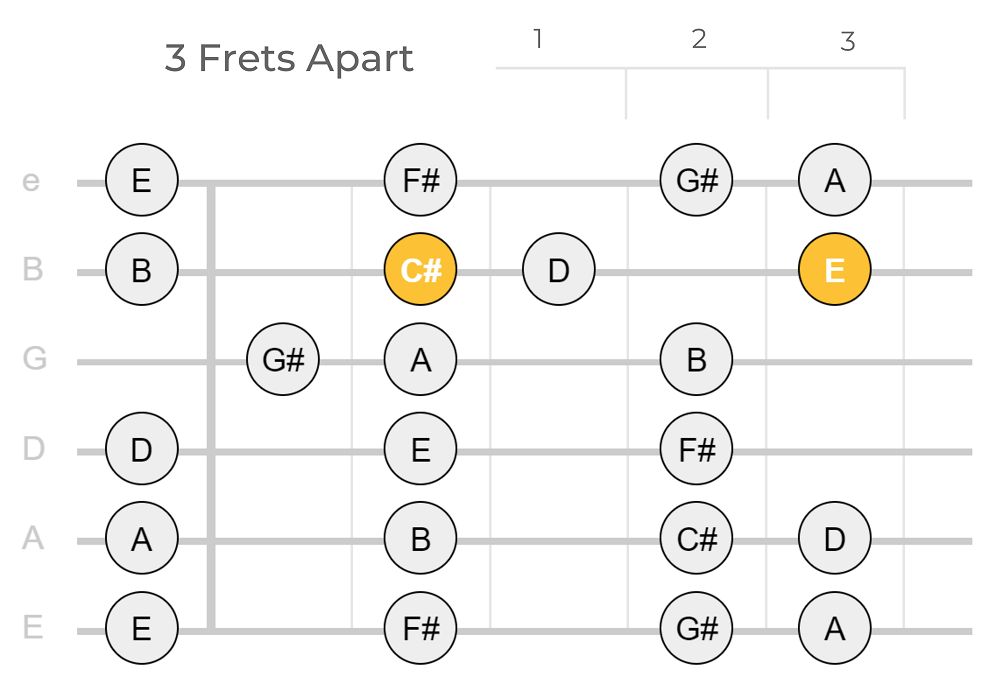

In guitar terms, is better to understand this by relating the concept of a “whole-tone” distance to being equal to 2 frets, and a semitone to being the same as 1 fret.

This means that every fret on your guitar is a half step (or one semitone) apart!

We can say, for example, that the B note is a whole-tone apart from the C# note, or that they are 2 frets apart in guitar terms, using the same formula.

Relative Minor Of The A major Scale

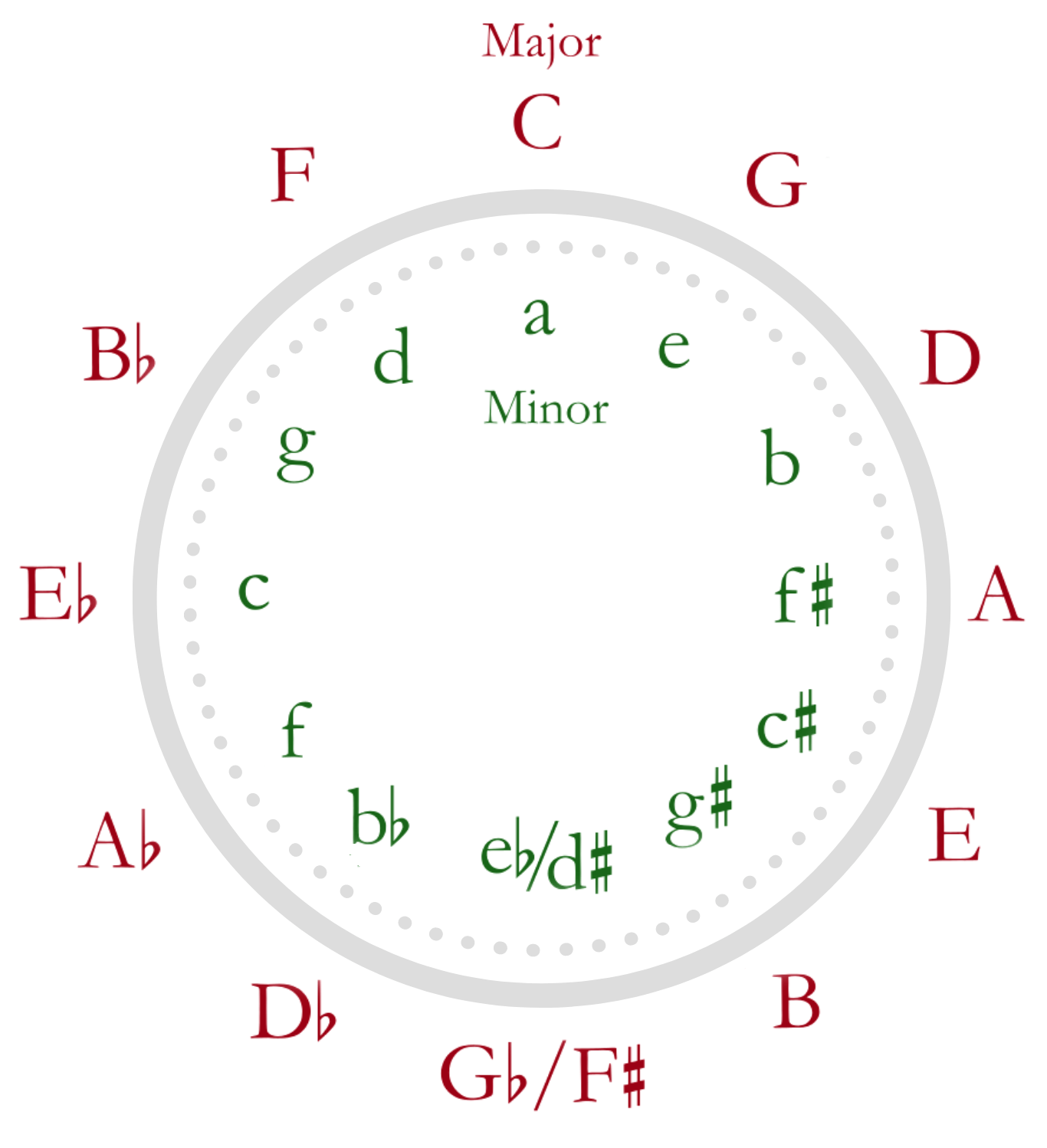

Just like we said at the beginning of this article, the relative minor scale of the A major scale is the F# minor scale and its parallel minor scale is the A minor scale.

The notes in the A major scale are identical to the ones in the F# minor scale but rather, the F# minor scale uses the F# note as its starting point (F♯, G♯, A, B, C♯, D, and E).

Such idea can be easily explained and illustrated through the Circle Of Fifths:

The Circle Of Fifths is a way of organizing the 12 chromatic pitches as a sequence of perfect fifths.

Regarding the question of whether these two scales are the same despite the fact that one is major and the other is minor…

The tonal center and focus of the A major and F# minor scales are different in that the A major scale’s tonal center and focus is A, whereas the F# minor scale’s tonal center and focus is F#.

In other words, while using the A major scale, most melodies will feel natural when they return to and rest on the A note, but in F# minor, they would eventually have to return to and rest on the F# notes.

Relative keys are the major and minor scales that have the same notes but are arranged in a different order.

The majority of songs written in the A major scale sound happy, upbeat, hopeful, and somewhat cheerful, whereas songs written in the F# minor scale sound serious, melancholic, and sad.

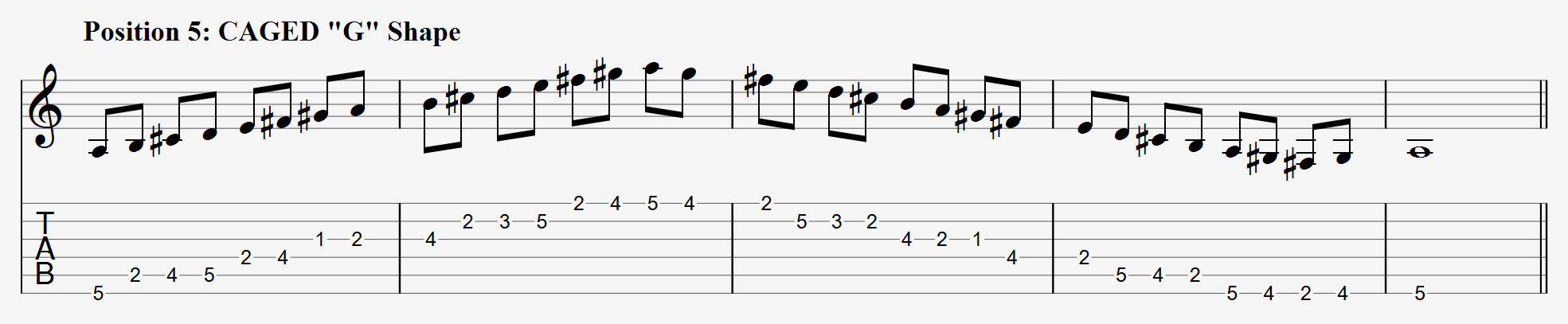

A Major Scale Guitar Fretboard Positions

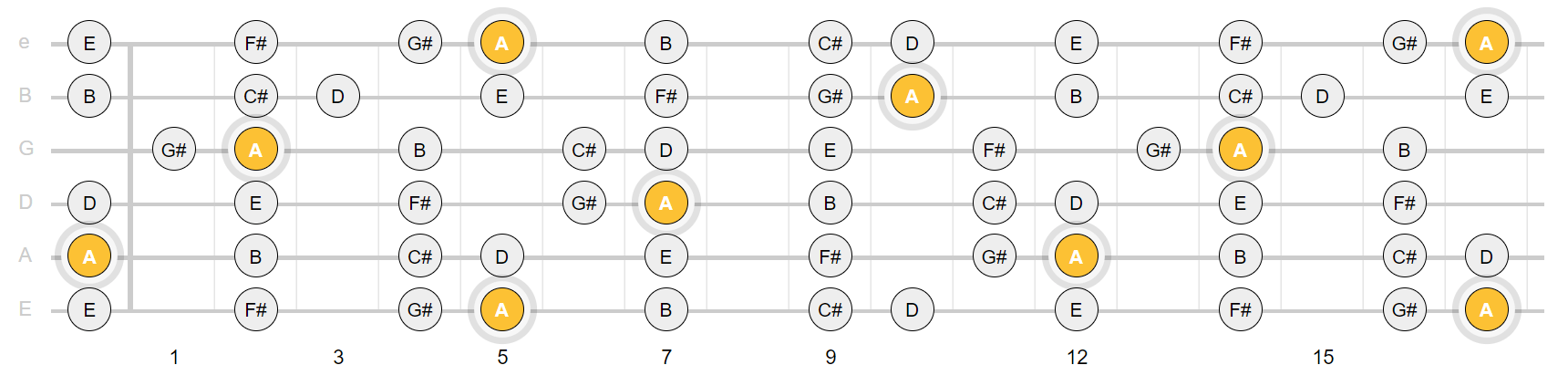

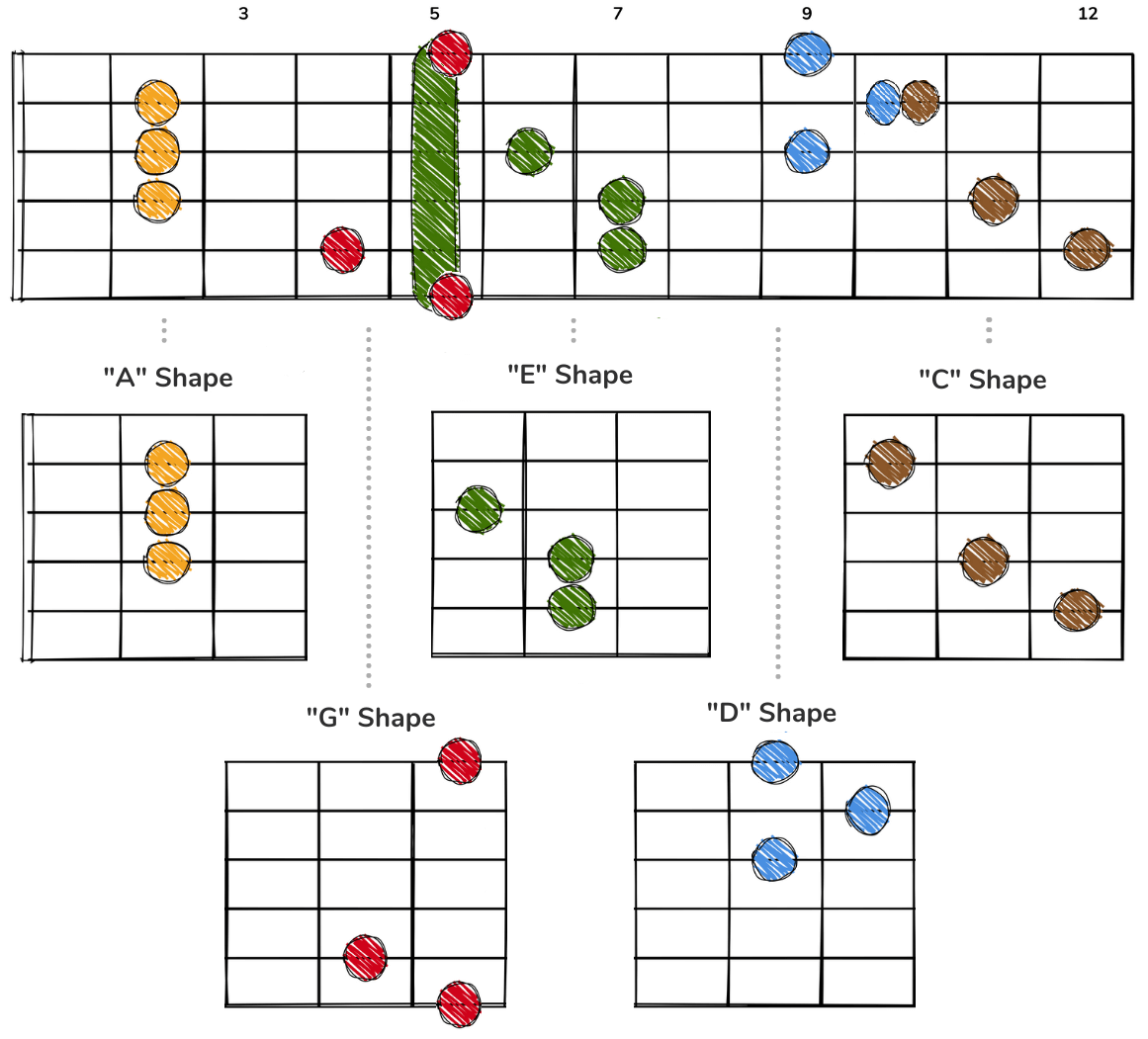

In standard tuning, the A major guitar scale can be played at many different fretboard positions.

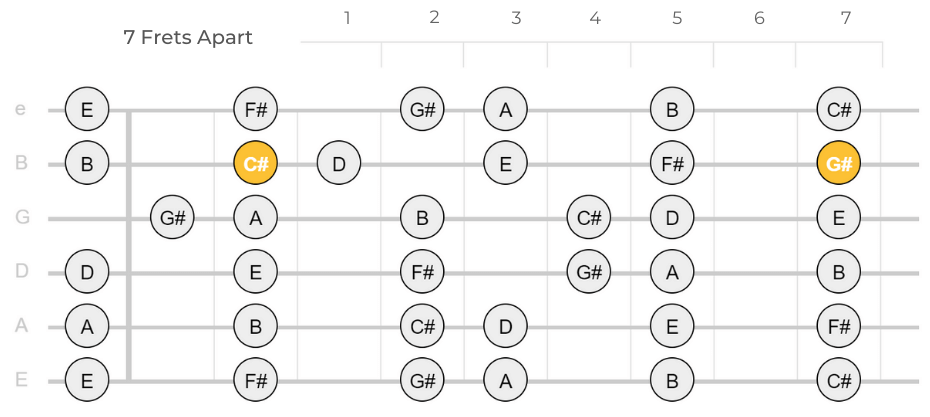

Take a look at the guitar fretboard screenshot below:

In yellow, you’ll find all the root notes across the entire guitar and you’ll notice that notes repeat themselves all over the fretboard.

There are many scale systems that you can use to play the A major guitar scale, the 3 most popular ones are:

- The CAGED Scale System

- 3 Notes Per String Scale System

- 7 Position Scale System

Each one of them has its own advantages and disadvantages, for example, the CAGED scale system is the more suitable choice for beginners as it doesn’t require a lot of finger stretching.

The ‘3 Notes Per String’ and the ‘7 Position Scale’ systems can be helpful in many cases as they allow you to stay in one position for more extended periods while moving quickly around the fretboard.

You should think of scale systems as just different ways of playing the notes on a given scale in different patterns.

Personally, I love the CAGED system since I think is the most practical one for learning chord shapes, arpeggios, and scales up and down the neck of the guitar.

See, the notes of the A major guitar scale that we showed in the fretboard screenshot above actually overlap with the notes of the A major chord in all of its many chord shapes in the fretboard.

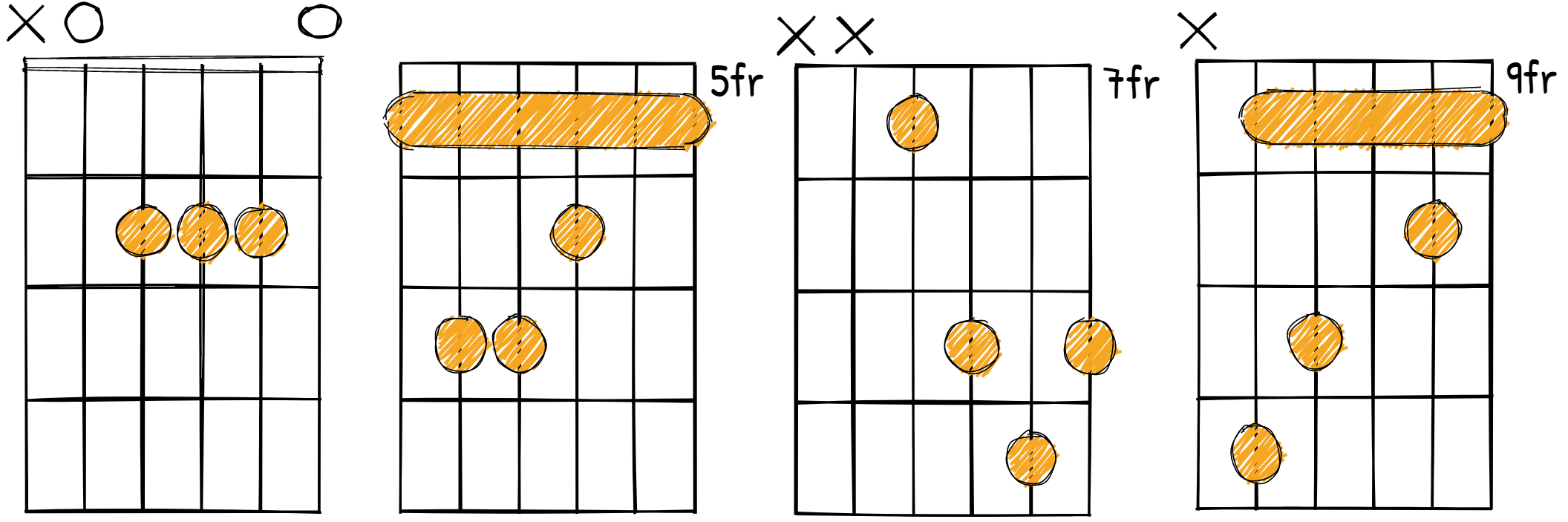

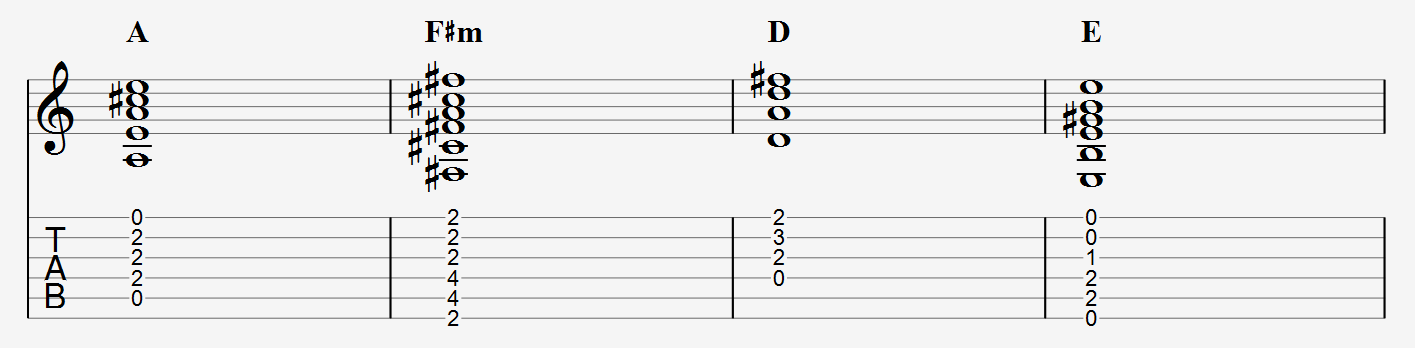

Just so that you can clearly visualize this idea, take a look at some A major chords that you can play on a guitar:

CAGED patterns are based on the open chord shapes of C, A, G, E, and D chords.

These are “moveable” scale shapes that you can use to play any other major scale by simply playing the same scale pattern starting from a different root note.

If you can play all of these chord shapes and master a particular scale and its patterns, you’ll then be able to play all of the other major scales as well.

The more you can see chords and scales in relationship to each other, the better you’ll be at remembering solos and chords and improvising in any key.

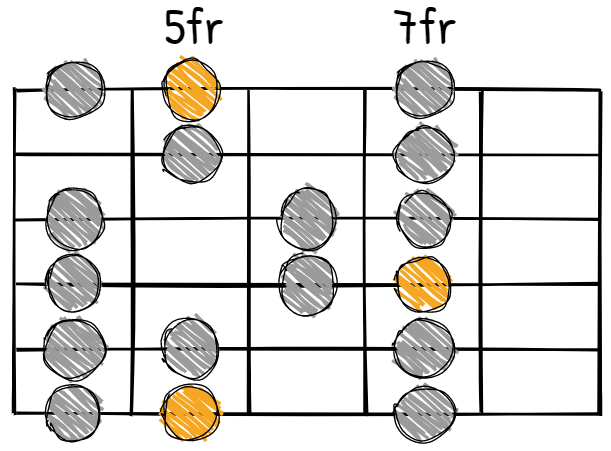

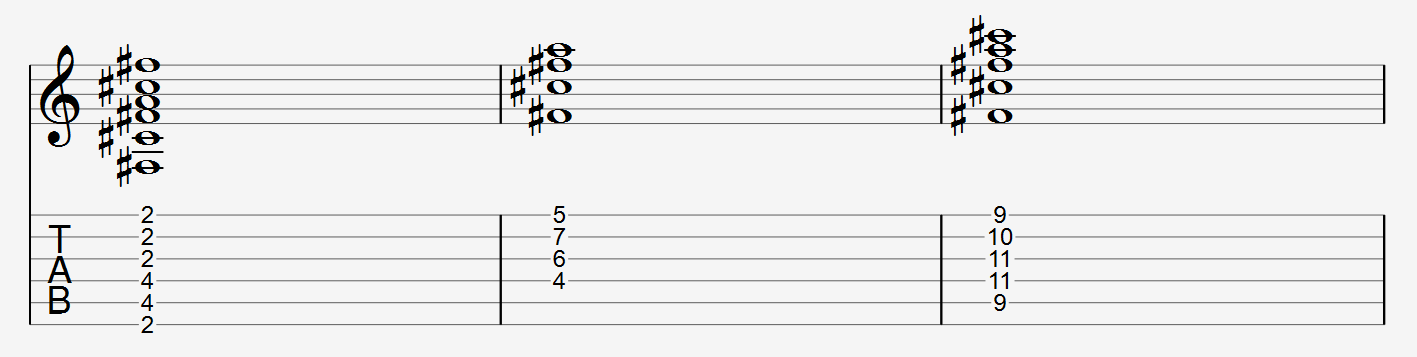

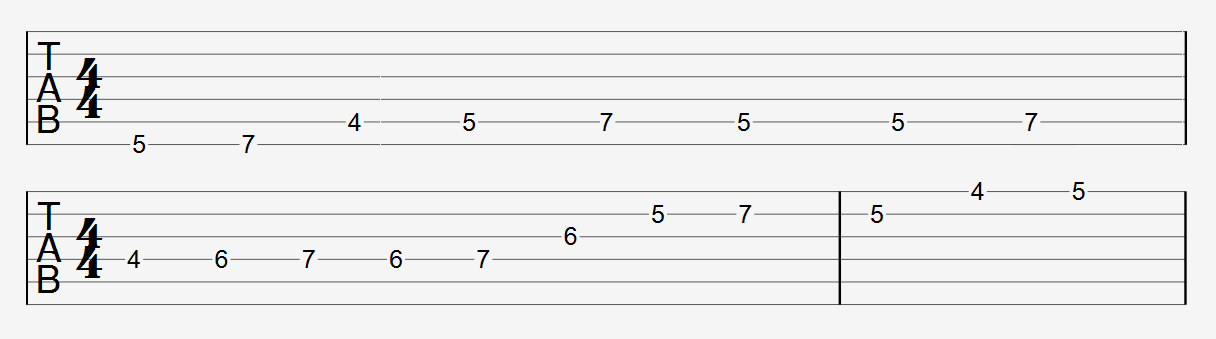

Position 1: CAGED “E” Shape

The CAGED “E” shape is the first position we’ll learn, which you can find by looking for the A scale root note on your guitar’s 6th string.

In this case, that will be on the 5th fret although the first note in this position starts on the 4th fret:

Now, for any scale, you’d typically want to begin playing from the lowest root note, and then play up to the highest note available.

Just so that you’re aware, the highest or lowest note available in the pattern doesn’t necessarily have to be a root note.

The highest note available in this position, for example, is on the 7th fret of the first string, rather than the root note in the 5th fret.

Now, after we played down to the lowest note available, we’d simply play our way back to the starting root note (if the lowest note in the diagram is not the root note, then we’d go to that one instead).

To put it another way, remember that when we started we technically skipped the first note, well, now we’re playing that note, and then we’re going to end in the same root note that we started.

If that’s a little confusing, then in tablature form is easier to understand this idea:

If you’re just learning how to play scales, go as slowly as you can and focus on accuracy rather than speed.

Then with the use of a metronome, start to speed up as you become more comfortable.

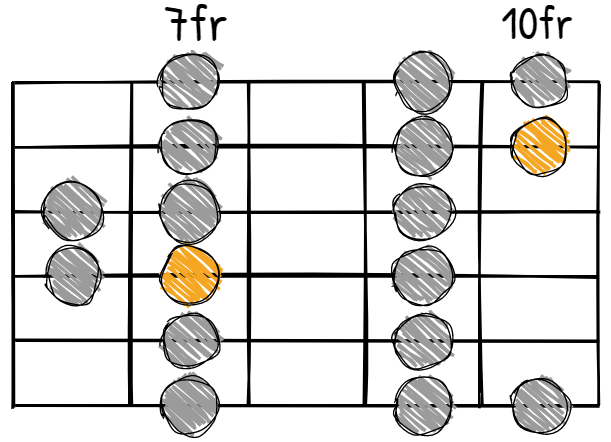

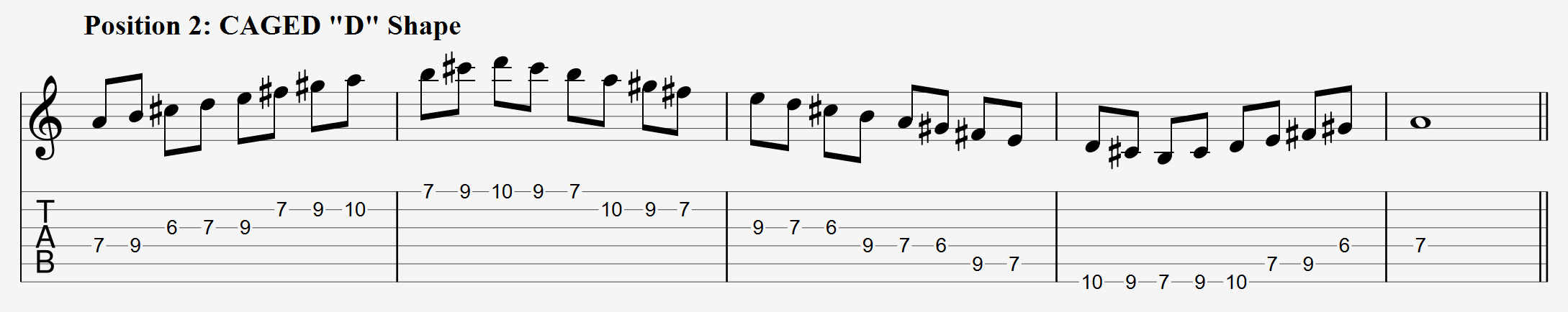

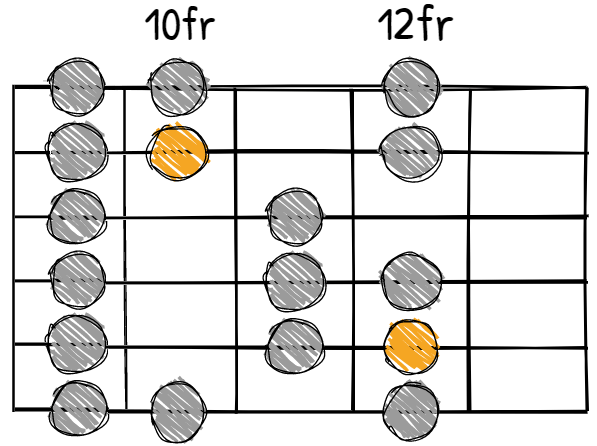

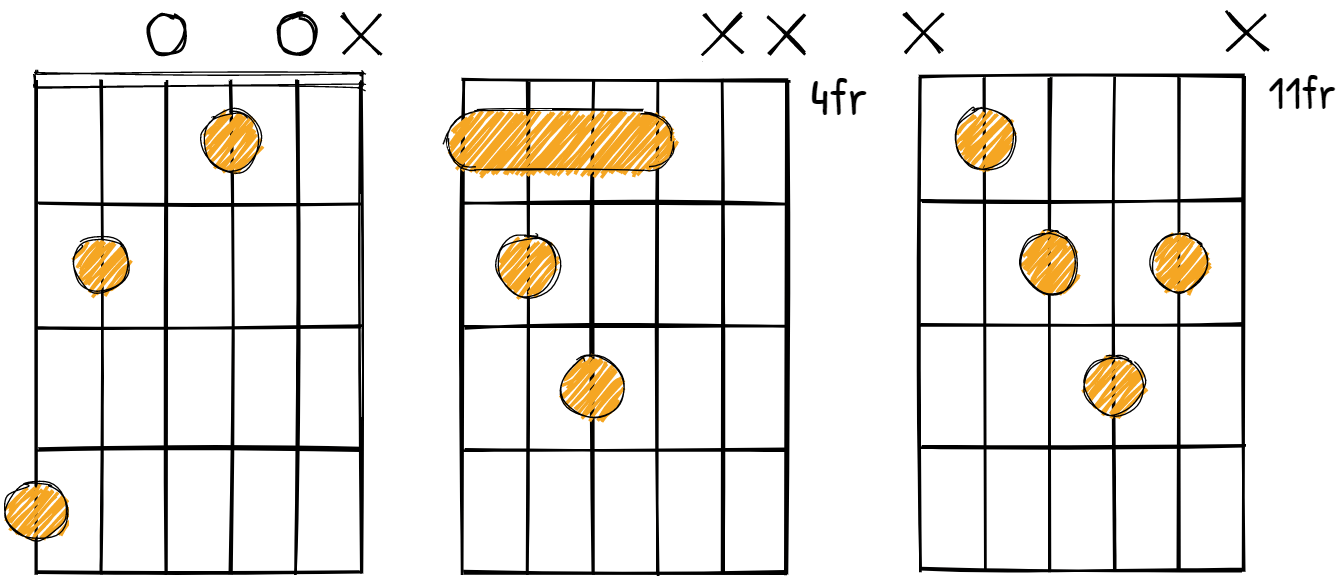

Position 2: CAGED “D” Shape

For the second position, we’ll be playing the “D” shape pattern of the CAGED system.

To find this pattern on your guitar fretboard, you can look for the A scale root note on the 4th string (D string) of your guitar.

The same ideas are happening here, the shape closely follows a D open chord shape with all the other notes from the A major scale side by side.

In tablature form this would give us something like this:

Just like in the previous position, we’re going to start from the lowest root note of the position, and then play up to the highest note available.

That would be on the 7th fret, 4th string, up until the 10th fret, 1st string, which again is also not a root note and it doesn’t actually have to be.

Once we reach this last note on the 10th fret, 1st string, we’d start to go back to the lowest note available, which for this position, in particular, is on the 7th fret, 6th string.

The lowest note available for this pattern is not a root note so in this case, we’re playing up again until we reach the starting root note.

If this note on the 7th fret, 6th string, was a root note, we would have been done right there.

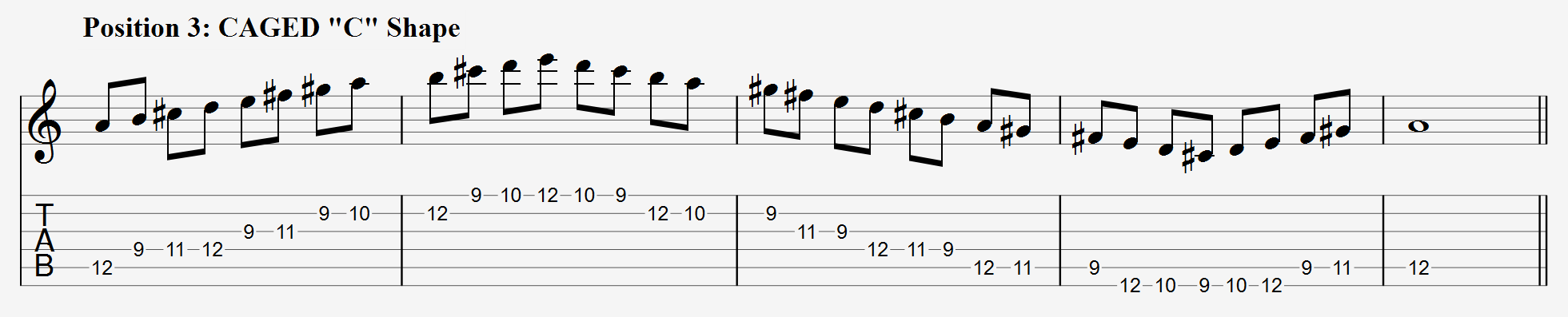

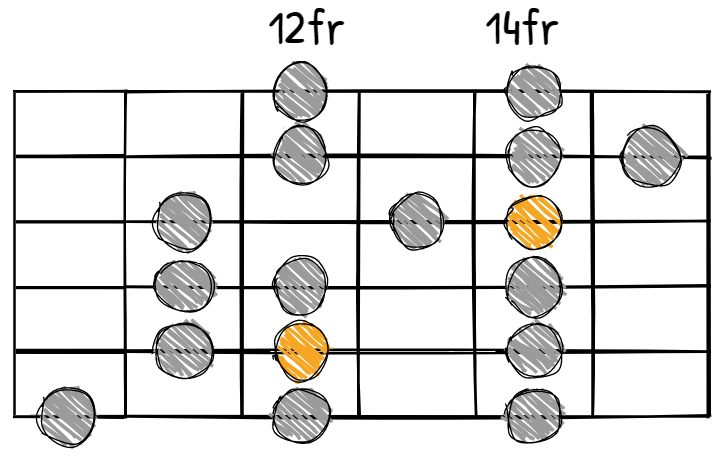

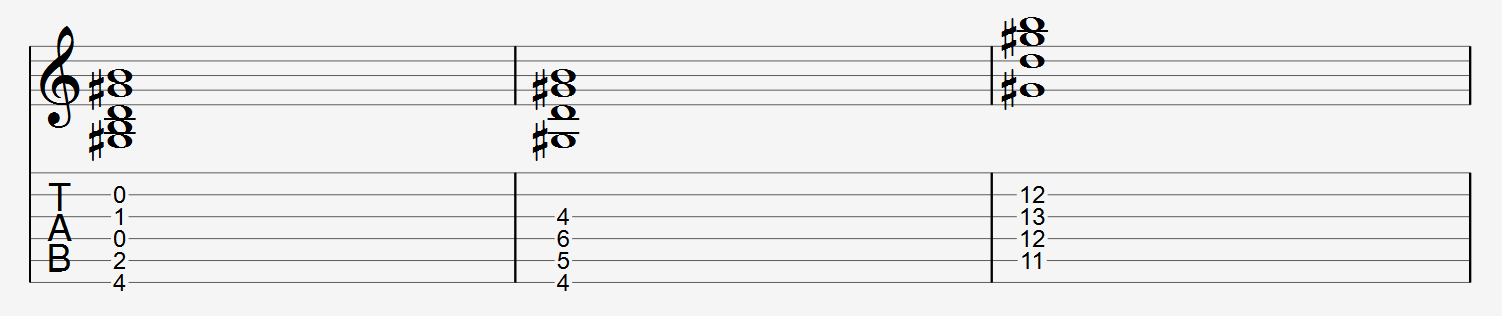

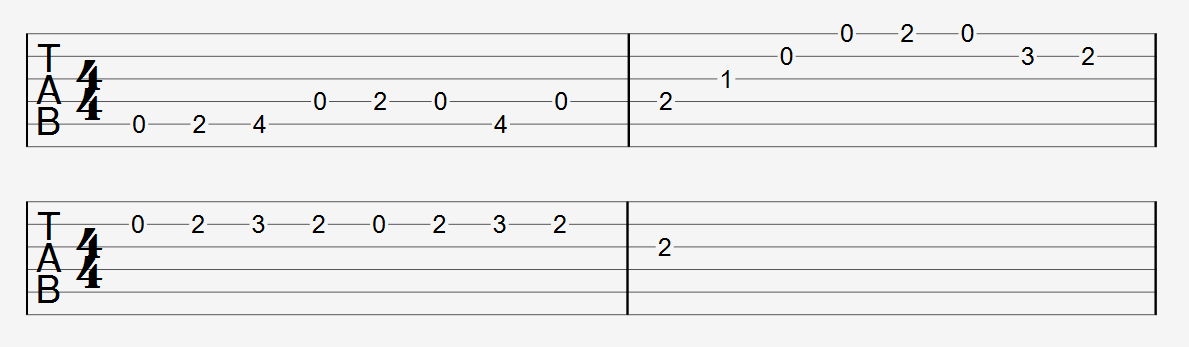

Position 3: CAGED “C” Shape

We’ll now see the “C” shape pattern, which corresponds to position 3 on the CAGED system for the A major scale.

The two root notes in this position are located in the 12th fret, 5th string, and the 10th fret, 2nd string.

If you’re wondering why the CAGED “C” shape is referred to as position 3 rather than position 1 (since the letter “C” is the first letter in “CAGED”), let me explain.

We generally number and name scale patterns based on which one has the lowest root notes.

In other words, out of all the patterns in a particular scale, the one that has a root note on the 6th string or the lowest root note of all, would be called pattern 1.

Putting this pattern in tab form would give us something like this:

If you look closely, you’ll notice that this position fits perfectly under your fretting hand.

For any beginner, if your hand hurts when you stretch it too far, I recommend starting with and learning this shape before any other.

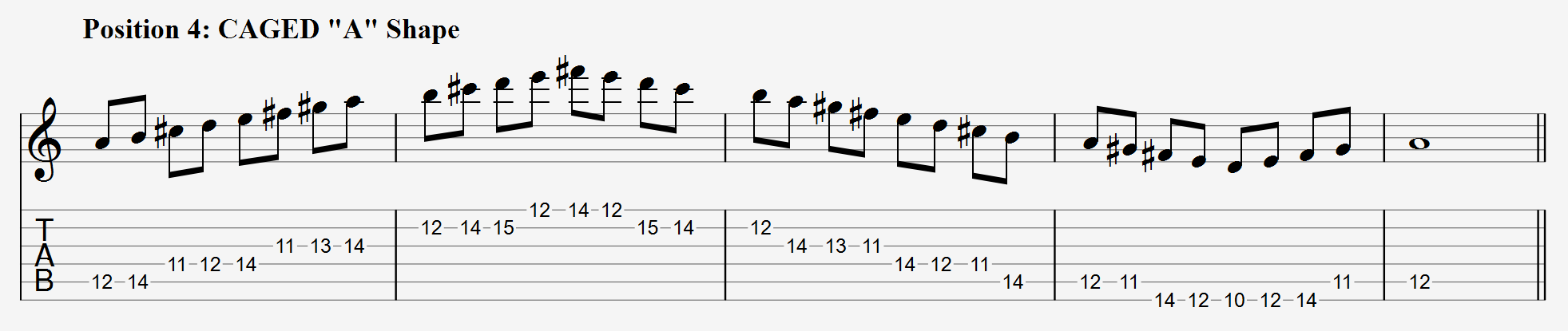

Position 4: CAGED “A” Shape

Because it spans 6 frets, the CAGED “A” shape position is the most difficult one to learn for most beginners.

Not only that, but it also plays 3 consecutive notes that are one whole step apart on the sixth string:

Now, out of all the shapes, this is the only one that people tend to play differently every time.

Some guitarists ignore the note on the 10th fret – 6th string and instead add a new note on the 16th fret – 1st string at the end of the scale pattern.

Others, on the other hand, choose not to play these notes at all and instead begin to play this pattern on the 12th fret – 6th string of their guitar.

In tabs, following all the same principles we’ve talked about before, we’d have to play something like this:

If you choose to play the 3 consecutive notes that are 1 whole step apart from each other and you’re not as comfortable doing so, then make sure to play as slowly as possible.

Concentrate on precision and accuracy first, and then gradually increase your speed when you feel like you can do so with no extra effort.

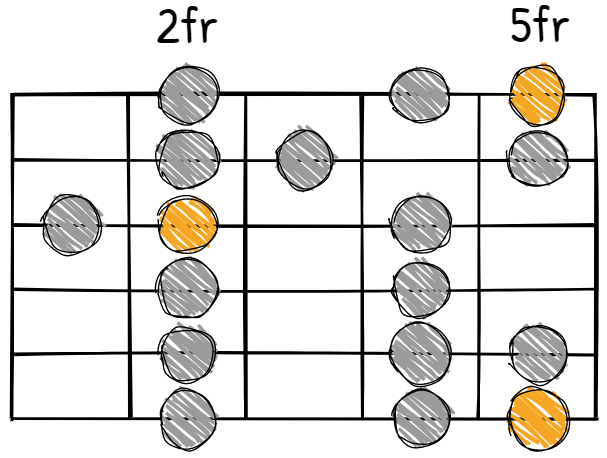

Position 5: CAGED “G” Shape

The “G” shape pattern will be the last position we will talk about.

This one, along with position 1, has the most root notes of all the shapes:

Having a lot of root notes to emphasize is great for those of you who want to improvise solos and create your own riffs using these scales.

This is because it allows you to find a lot more patterns and licks that you can later memorize and play whenever needed.

This scale would give us something like this in tablature format:

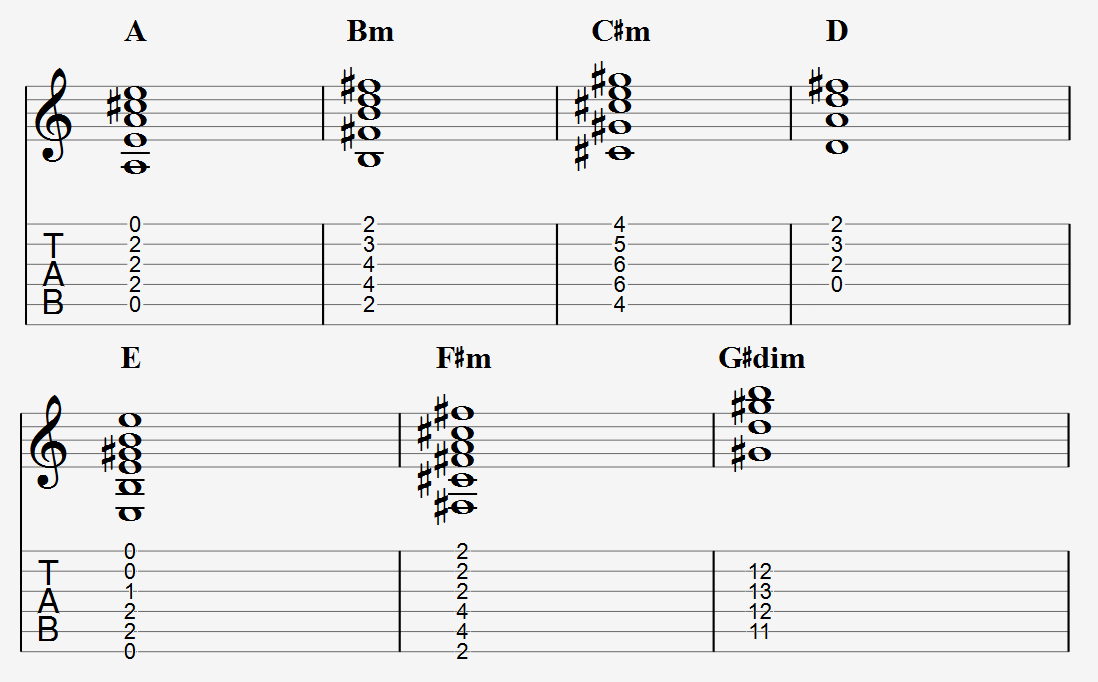

Chords In The A Major Scale

In this section, we’re going to show you the 7 chords that come from the A major guitar scale.

With the 7 notes (A B C# D E F# G#) of the scale, you can get a group of chords built from those same notes.

The 7 chords in the A major scale are:

- I – A major (A)

- ii – B minor (Bm)

- iii – C# minor (C#m)

- IV – D major (D)

- V – E major (E)

- vi – F# minor (F#m)

- vii° – G# diminished (G#dim)

The first 6 chords are used all the time in many popular songs we hear every day.

Now, you may be thinking: how are these chords in specific related to the A major scale?

This is an excellent point, and many articles on this subject fail to explain it.

Take a look at the table below summarizing the chords in the A major scale and their notes:

| Chord | A | Bm | C#m | D | E | F#m | G#dim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notes | A-C#-E | B-D-F# | C#-E-G# | D-F#-A | E-G#-B | F#-A-C# | G#-B-D |

These notes are not random, they are triads, meaning a given note in the scale with its third and fifth above it.

So for example, taking the 7 original notes of the A major scale, A B C# D E F# G#, if we wanted to assemble our first chord, we’d do the following…

Take the first note (A) in the scale and look for its 3rd (two notes up) and its 5th (moving up another 2 notes up from the third) on the scale.

That gives us A, C#, and E, also known as the A major chord (A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G#).

For the second, third, and all the other chords, you’ll need to take the respective root note and find its third and fifth.

| A | B | C# | D | E | F# | G# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A major | 1 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| B minor | 1 | b3 | 5 | ||||

| C# minor | 1 | b3 | 5 | ||||

| D major | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| E major | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| F# minor | b3 | 5 | 1 | ||||

| G# diminished | b3 | b5 | 1 |

In the table above, just know that 1 = root note, 3 = third, b3 = flat third, and finally 5 = fifth.

To summarise it all, it would end up being something like this:

- A major chord (A-C#-E): A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G#

- B minor chord (B-D-F#): B – C# – D – E – F# – G# – A

- C# minor chord (C#-E-G#): C# – D – E – F# – G# – A – B

- D major chord (D-F#-A): D – E – F# – G# – A – B – C#

- E major chord (E-G#-B): E – F# – G# – A – B – C# – D

- F# minor chord (F#-A-C#): F# – G# – A – B – C# – D – E

- G# diminished (G#-B-D): G# – A – B – C# – D – E – F#

Lastly, before taking a closer look at all these chords one at a time, let’s briefly talk about why some chords in the scale are major and others minor.

On any major scale, the pattern will be:

major, minor, minor, major, major, minor, diminished

You can either memorize that or learn that the intervals (distance in pitch between any two notes) of the scale dictate whether a major 3rd (3) or minor 3rd (b3) is used above a given degree’s root.

The distance from the root note between the notes in the chord determines whether the chord is a major, minor, or diminished chord.

- A major chord is formed from a major third (4 frets apart from the root note) and a perfect fifth (7 frets apart from the root note).

- A minor chord is formed from a minor third (3 frets apart from the root note) and a perfect fifth.

- A diminished chord is formed from a minor third and a diminished 5th (6 frets apart from root note).

If that’s confusing to you, you’re not alone, it didn’t make sense for me at first either.

Let’s take a look at an example:

With the C# note in the A major scale, we learned that by finding its triads, the notes of the chord are C#, E, and G#.

If you measure the distance between any C# (the new chord root note) and E notes on your guitar, that will be 3 frets or a minor third.

Now if you measure the distance between any C# (the new chord root note) and G# notes on your guitar, that will give you 7 frets or a perfect fifth.

Going back to what we just mentioned above, for a chord to be a minor chord, there needs to be a minor third and a perfect fifth.

So in this case, the chord that we form with the C# note would be minor (C#m).

Again, if you’re just learning about scales, I wouldn’t suggest going all in trying to figure out why these concepts work the way they do.

For most experienced guitarists, this information is very useful to know, but for beginners, it can be tough to learn right away.

A Major Chord

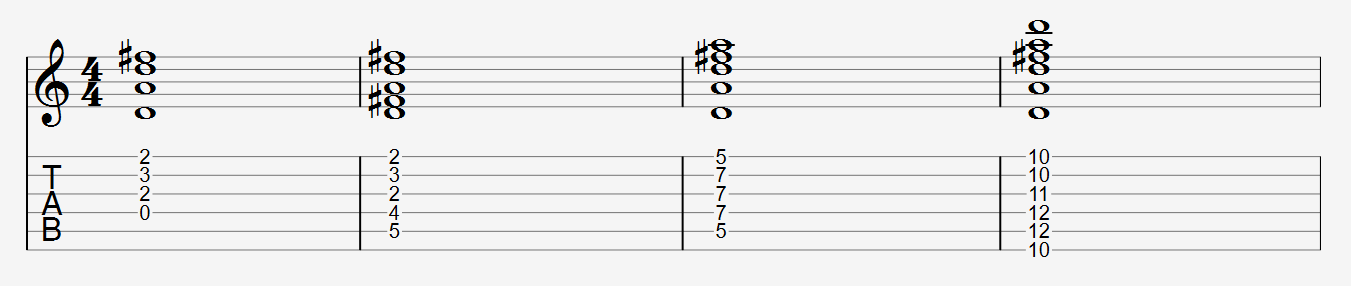

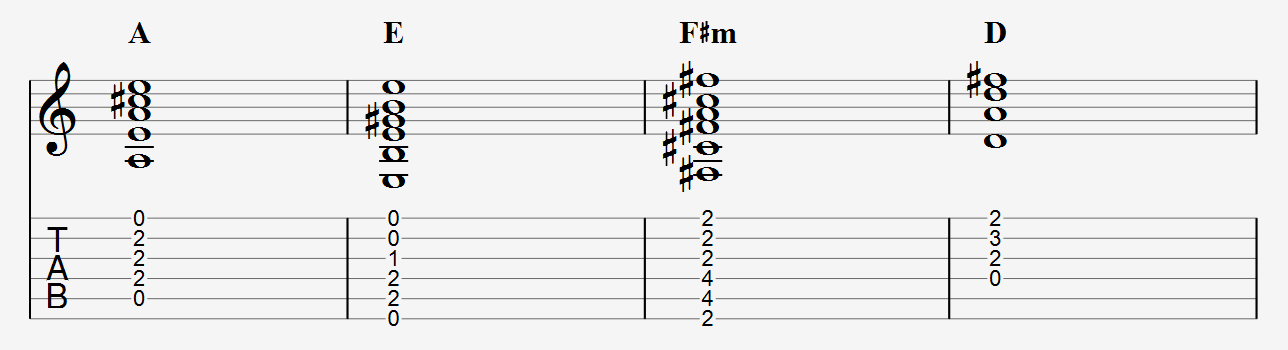

We’ll start with A major (I) and its several chord shapes up and down the neck:

If you’ve been playing guitar for a long time, you should be able to recognize the first chord; it’s almost always one of the initial ones we learn.

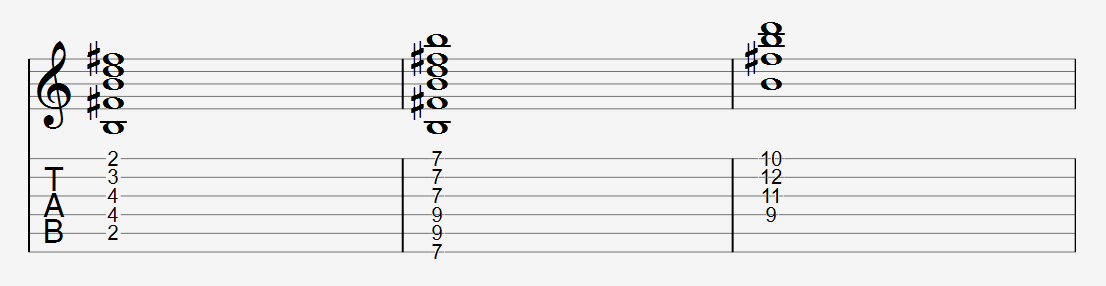

For those of you that might be more comfortable reading tabs, this might help:

What I want you to pay attention to is the relationship between the scales we saw before and these chords.

Go back to the previous section to see how they all fit together flawlessly, and how every note in these chords is part of the fretboard diagram at the start.

This may seem obvious to many people, but if you’ve failed to grasp music theory in the past, it can be a powerful a-ha moment.

B Minor Chord

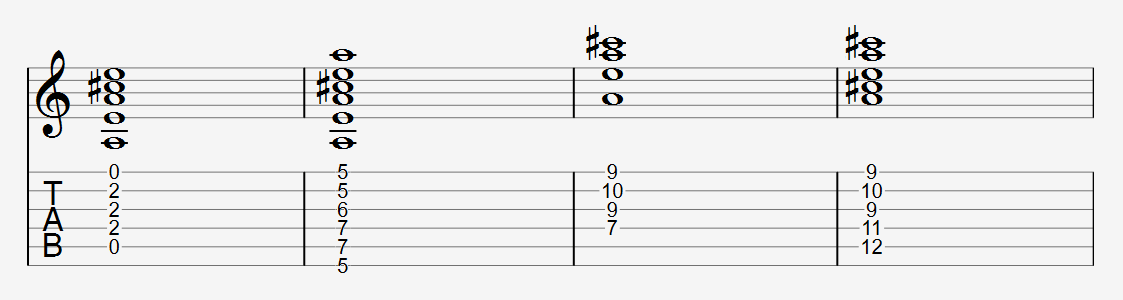

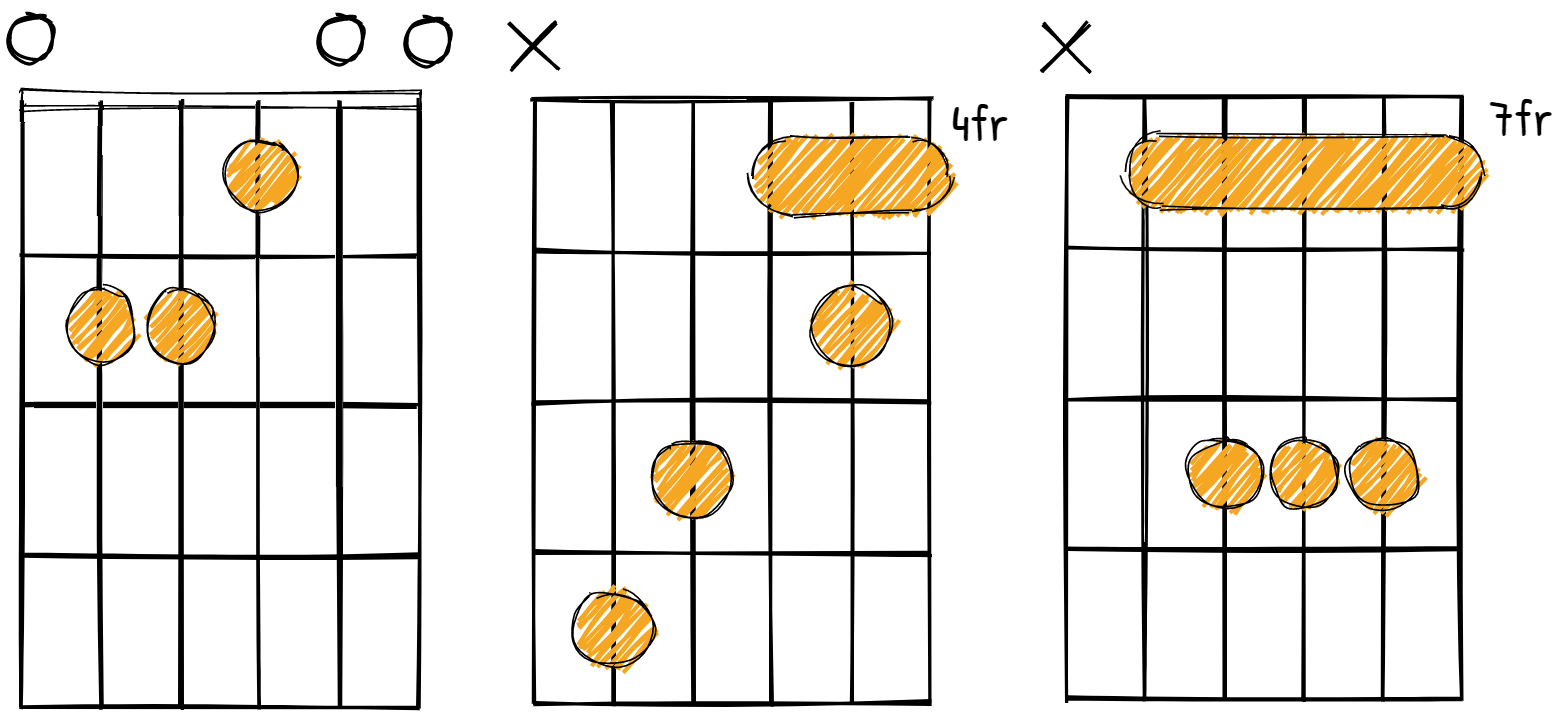

This time, let’s take a look at the Bm (ii) chord and its most popular chord positions:

And here is the tabs of each one of these chord shapes side by side:

B minor chord is a triad chord composed of the notes B, D, and F#.

This chord is used to create sad or melancholy sounds in music, and knowing the different shapes across the fretboard will allow you to add a lot more variation to your songs.

C# Minor Chord

If you took the time to play the last chord we discussed, then this one will feel remarkably similar because it’s the same shape just two frets away.

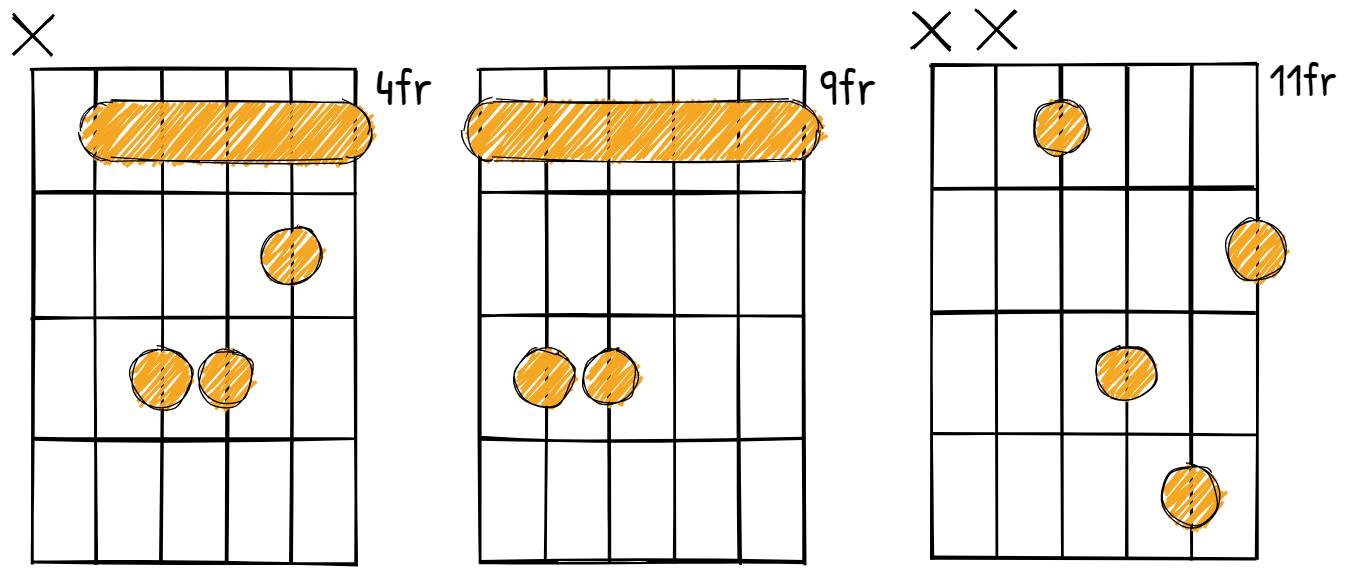

Take a look at these C#m (iii) chord diagrams across the guitar fretboard:

Although there are many other shapes aside from these 3, these are among the most used ones.

Going back to the idea of learning and memorizing all these chords, you start to realize that the easiest way of doing so is to pretty much learn the shapes rather than remembering all the positions.

Once you understand that you can find the root note of a chord in either the 5th or 6th strings and play a barre chord with an A minor and E minor chord shape respectively, you’ve already learned all the possible minor chords.

D Major Chord

Now let’s move to the next chord that comes from the A major guitar scale, in this case, the D major (IV) chord.

The first shape is another example of one of the most typical chords you’ll encounter as a guitar player.

When it comes to the second chord shape, although people use it less frequently, it’s still a popular alternative that guitarists use when making chord transitions and progressions.

Here are the same 4 chord shapes in tablature form:

If you’re a beginner, I would discourage you from learning the second shape until you feel more comfortable and gain more experience as a guitarist.

The finger stretching in that type of position can hurt your hand badly and it’s simply not that worth it when you’re starting out.

E Major Chord

The next chord that we’ll talk about is the E major chord (V).

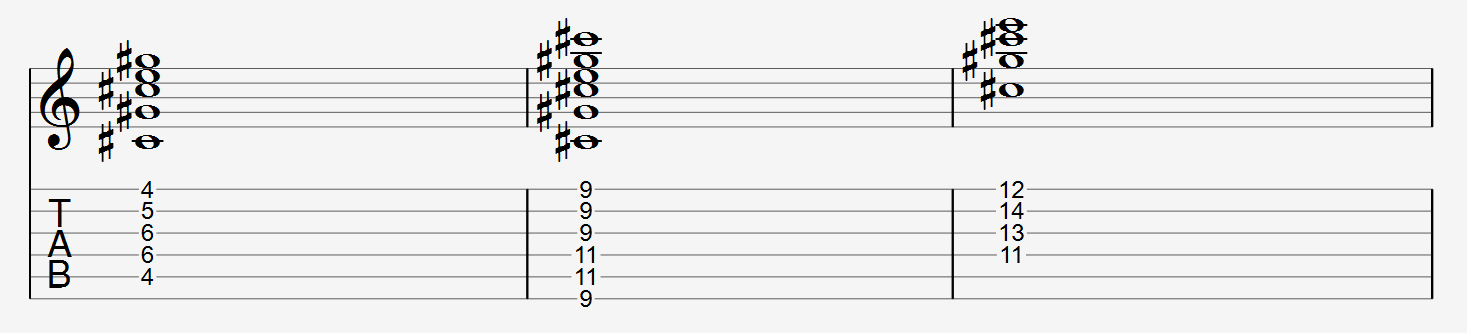

Here are 3 different shapes that you can play across the guitar fretboard:

In tablature form, these 3 chords would look something like this:

To play the most used E major chord shape on the guitar, you need to put your first finger on the 3rd string – 1st fret, second finger on the 5th string – 2nd fret, and lastly your third finger on the 4th string – 2nd fret.

The root note of this chord is on the open note of the 6th string, so you should strum all the strings whenever you’re playing the first shape in particular.

F# Minor Chord

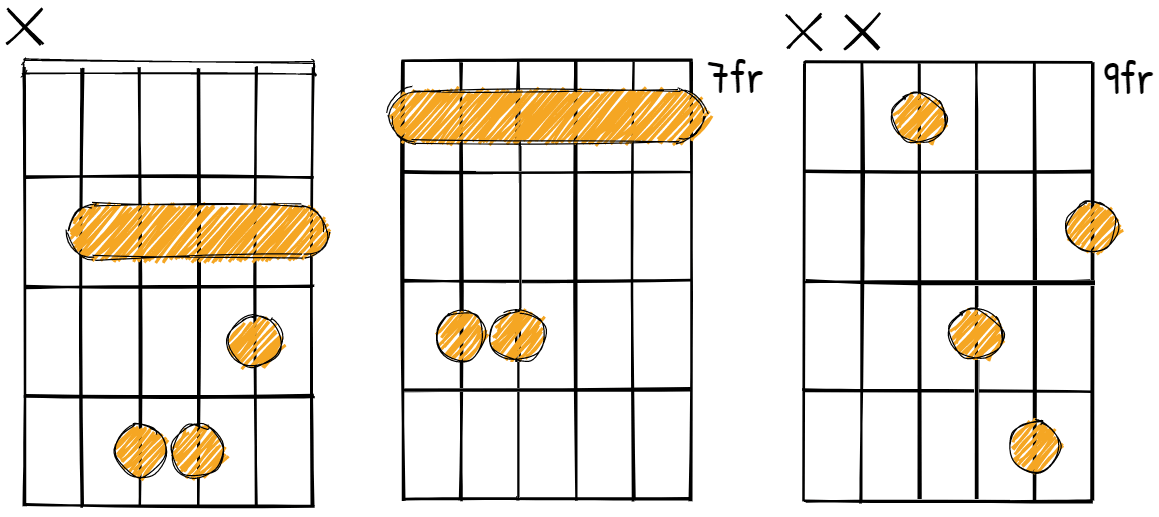

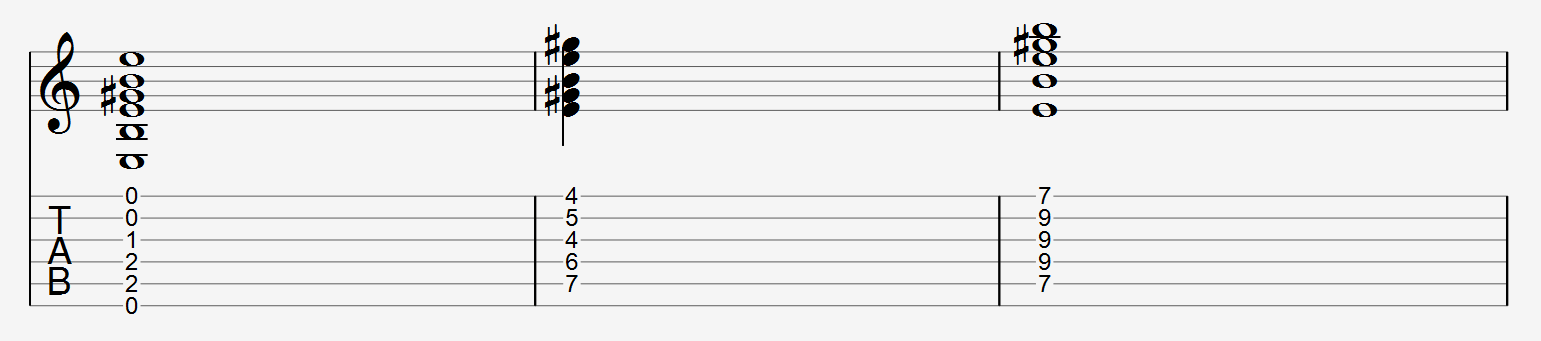

Let’s now take a look at some F# minor (vi) chord diagrams:

In the key of A major, this chord holds a special place since the relative minor key of the A major key is the F# minor key.

In tablature form, these F# minor chord variations can be represented like this:

Once again, knowing the different chord shapes across the fretboard is very practical when memorizing the actual scales as it allows you to see and understand the theory behind them.

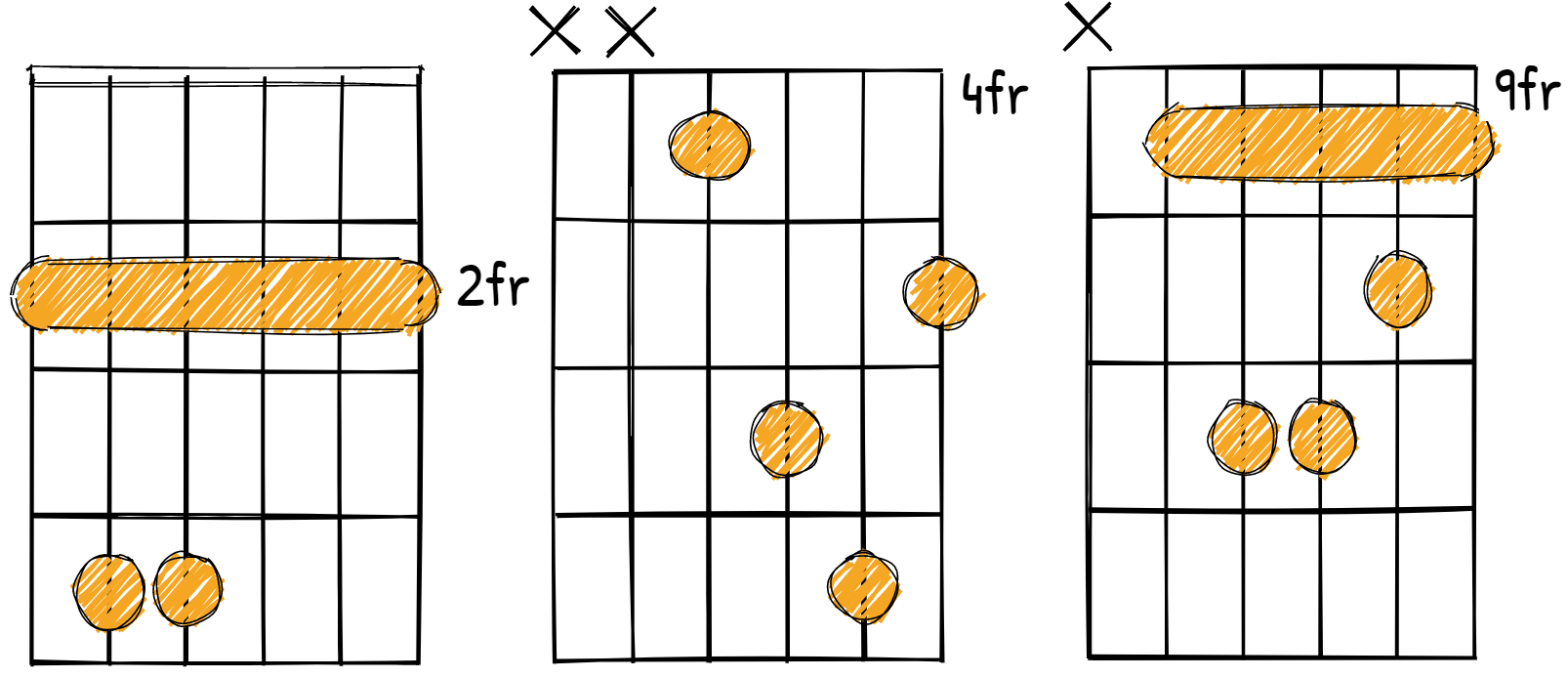

G Sharp Diminished Chord

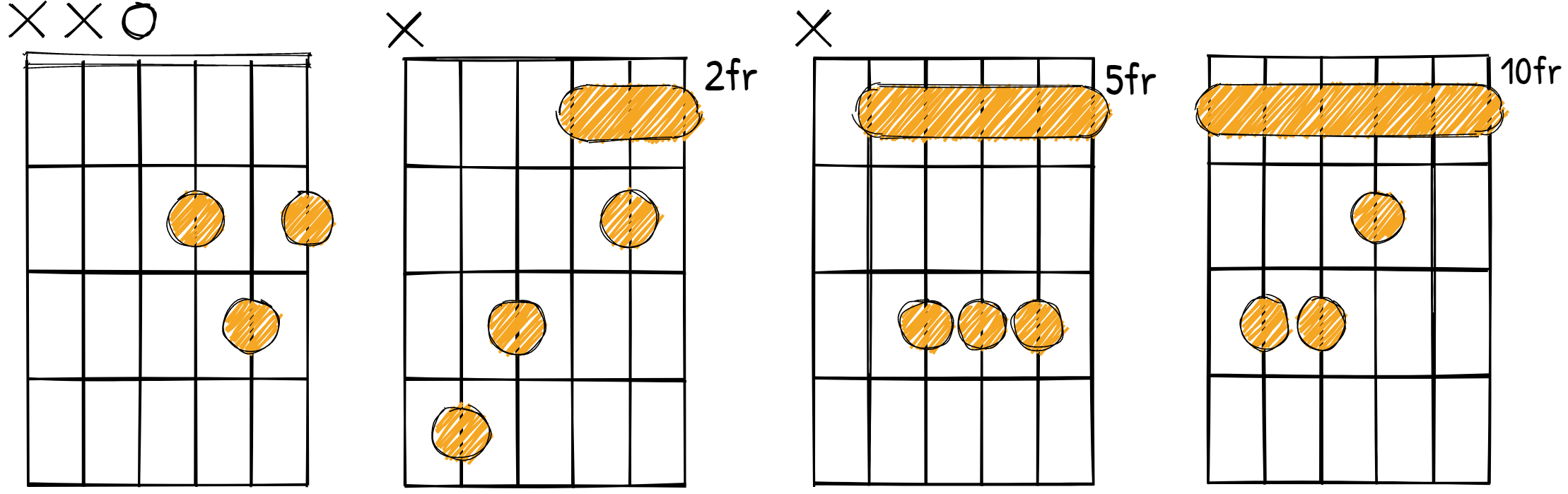

Lastly, we’re going to take a look at some G# diminished chord variations (vii°), here are 3 of the many different shapes that you can play:

The first shape is in my opinion the easiest one to play, although I love how the 2nd and 3rd chord ones sound by far.

Many online articles simply ignore this type of chord when they do a beginner-friendly tutorial about major scales; we believe that you should certainly know about it.

In tablature form, these G# diminished chord variations can be illustrated like this:

When playing these chords, make sure you pay attention to whenever a string doesn’t have to be played, that is an X for diagrams and an empty string for tabs.

This is very important to make sure you’re not playing notes outside of the A major scale.

You should definitely watch this YouTube video by Worship Tutorials on chord voicings in the key of A major:

What he teaches in this video, in my opinion, is a great first step in advancing from beginner to an intermediate guitar player when it comes to guitar chords.

Using different chord voicings not only makes your playing unique but also opens the door for very intriguing and beautiful melodies for you to find and write.

Guitar Exercises In the A major Scale

Now let’s play some guitar exercises to help you both remember these scales and chords and increase your accuracy when doing so.

For the first two exercises, we’re going to play different chords in the scale of A major, and for the other two, we’re going to come up with our own guitar licks using what we’ve learned so far about the CAGED system scale positions.

Exercise 1

The first exercise is very simple, we’re just going to play all the chords in the A major key one by one.

What I want you to do is play this a couple of times so that you get a sense of what each chord represents when played along with the other ones.

After you do so, before jumping into exercise 2, I challenge you to come up with your own chord progression just by using your intuition.

Start altering the order in which you play these chords and create progressions of only 4 or 2 chords.

You can go back to the chord diagrams and use different variations across the fretboard.

Exercise 2

Now, for exercise 2, we’re going to go over one of the most popular chord progressions in the key of A major, that is A-F#m-D-E or I-vi-IV-V.

Did you by any chance play this on exercise 1?

Nevertheless, you might be able to hear some similarities between these chords and those from the so popular “Stand By Me” by Ben E. King.

Exercise 3

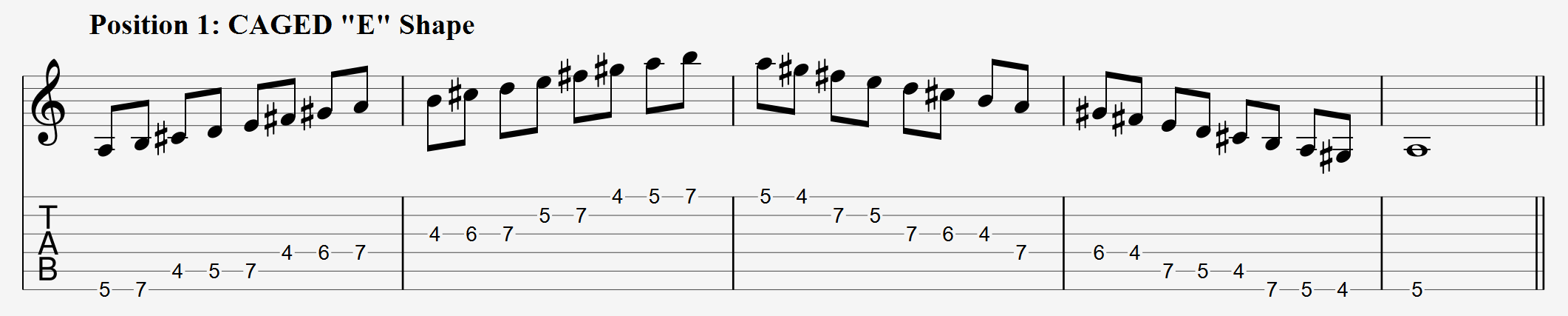

Our third exercise is based on the CAGED “E” shape.

Instead of playing the scale like we normally would, this time we’re going to create our own guitar lick with the help of the scale itself.

A lot of lead guitar playing is going to involve using the information in chords and scales to create our own melodies.

I advise you to play these as slow as you can with the help of a metronome and start increasing your speed up as you get more comfortable.

We often just focus on playing scales right from a diagram and ignore all the musical information contained therein and how to use it in real scenarios.

Hopefully, this exercise shows you how by simply looping a specific pattern over and over, or by changing the order in which you play a scale you can begin to grow your soloing skills.

Exercise 4

Our last exercise is my favorite one out of all the other ones that we’ve played so far.

This exercise is based on the CAGED “E” shape.

Before you even attempt to play it, you must know that this is an accuracy exercise, in other words, it’s not meant to be played fast at all.

I advise you to also play it very slowly with the help of a metronome starting at 60-70 bpm and then increase your speed by 5bpm each time.

For low-experienced players, working on accuracy alone will make a huge difference in how much progress is made in their overall mastering of the guitar.

Here’s an awesome backing track in the key of A major that you can use to put together everything you’ve learned so far:

This video will show you the chords that the rhythm guitar is playing and will also provide you with the A major scale notes across the entire fretboard.

You should use that information to alternate between rhythm and lead guitar, and go from playing chords to soloing every so often.

Chord Progressions In The A major Scale

It’s time to have some fun and talk about chord progressions in the A major scale.

Use these to build your song repertoire and study how other musicians have used the information that we just presented to you in actual songs.

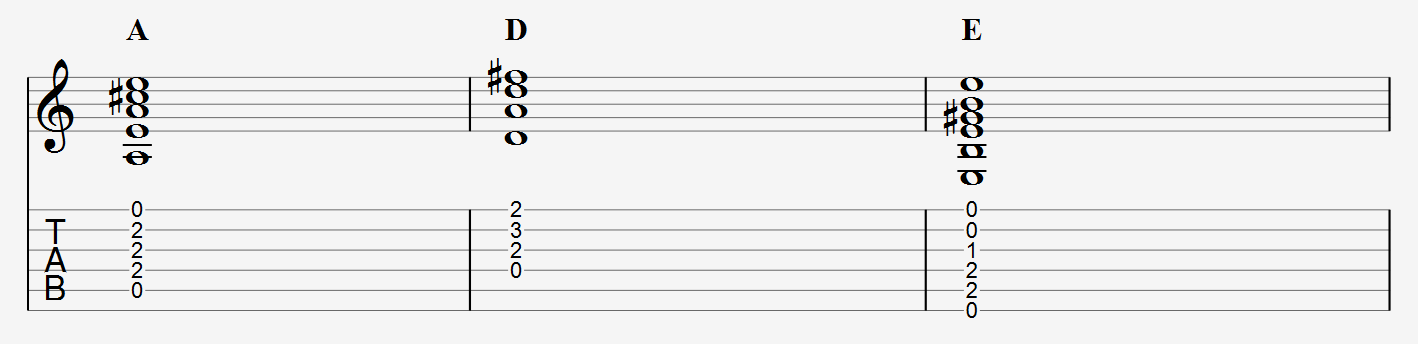

A – D – E

Our first example will be a very beginner-friendly progression of open chords following the pattern I-IV-V.

These chords, when put together sound naturally joyful, happy, and come full of positive energy.

We’ve all seen it happen, again and again, three chords are all it takes to make a hit song, and that’s in any genre ranging from rock, blues, funk, and pop.

To change the feel of the progression and make it sound more interesting while playing, you can alternate between playing the open, barre, and power chords variations.

A – E – F#m – D

This chord progression is one of my personal favorites, it follows an I-V-vi-IV pattern.

Even though it’s one of the most popular chord arrangements ever, it’s still undoubtedly beautiful.

Something cool about these chords is that no matter the order in which you play them, they’ll always sound right.

With that being said, here are all the possible variations you can play:

- A-E-D-F#m

- A-F#m-D-E

- A-F#m-E-D

- A-D-F#m-E

- A-D-E-F#m

Switching around and coming up with your own patterns is a very simple way of making any boring song a little more enjoyable.

You can also use a different option for different parts of a song such as the verse and chorus.

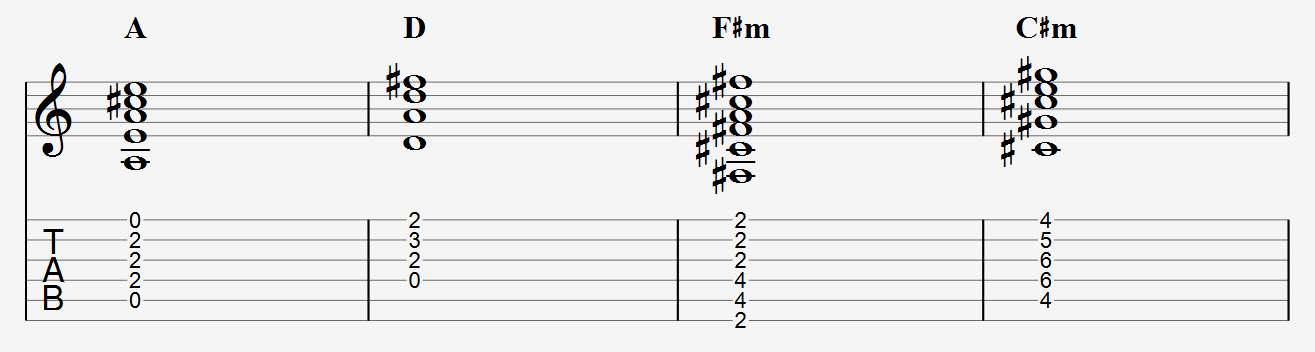

A – D – F#m – C#m

Lastly, we’ll play a chord progression that uses the C#m chord in the key of A major and follows an I- IV- vi-iii pattern.

This one is very similar to the previous one but it goes to show how any combination of chords can be a new idea to implement.

Once again, I encourage you to change the order of the chords and see what you’re able to come up with.

A few songs that were written using the A major scale are:

- “Wonderwall” by Oasis

- “Someone Like You” by Adele

- “Africa” by Toto

- “Pompeii” by Bastille

- “Billie Jean” by Michael Jackson

- “Rock and Roll” by Led Zeppelin

- “Tears in Heaven” by Eric Clapton

- “Here Comes the Sun” by The Beatles

- “Dancing Queen” by ABBA

- “Chasing Cars” by Snow Patrol

- “My Immortal” by Evanescence

Dad, husband, son, and guitarist. I’ve been playing guitar for 20 years. Passion for writing, painting, and photography. I love exploring nature, and spending time with my family. Currently have a Gretsch G5220 Electric Guitar as my main instrument.