The minor key is a wonderful yet terrifying mix of beauty and darkness in many contexts.

It holds the key to many of the most powerful musical sounds you’ve ever heard, and it can be a great tool in the hands of a songwriter who wants to wield it.

It’s not just the domain of modern music, though; the 12 minor keys have been used ever since the time of Bach.

Today, it still dominates the sounds of many genres like delta blues, thrash metal, country rock, pop, psychedelia, and shoegaze amongst many others.

In this post, we’ll take a look at some of the most popular minor chord progressions of all time and how they were used to create truly amazing sounds.

Table of Contents [show]

Minor Chord Progressions

i – iv – III – VI

Many minor chord progressions in rock music will not use a full harmony but instead, use power chords.

It implies the dark sound of minor without adding all the third intervals.

This riff by Nirvana is played in the key of F minor, and it goes as follows:

- F minor scale = F – G – Ab – Bb – C – Db – Eb

- F5 (i) = F – C

- Bb5 (iv) = Bb – F

- Ab5 (III) = Ab – Eb

- Db5 (VI) = Db – Ab

Also, notice that it doesn’t use the v chord to end on.

Although many progressions in minor keys will end on a minor v or a major V, this will create a classical baroque sound that you may not want.

This riff can also be seen as a series of I-IV changes in F and then in Ab.

If any of this is difficult to understand, it’s because you haven’t taken the time to learn the fundamentals of music theory yet.

It doesn’t matter whether Kurt knew any of this when he wrote the riff.

There is no debate that the riff follows and uses many of the notes and possible sounds of a minor key, and it will do you immense good for your playing and songwriting to continue reading this article.

ii – (I – V)

You can see this progression in two ways: as a progression in A Dorian or as an A Minor progression with a major IV chord.

Like last time, we can break down the scale and chords to see this:

- A Dorian = A – B – C – D – E – F# – G

- G Major = G – A – B – C – D – E – F#

- Am (ii in G major) = A – C – E

- G (I) = G – B – D

- D (V) = D – F# – A

- A Minor = A – B – C – D – E – F – G

If you’ve been looking for an example of modes in music, then here is one for you.

Playing a modal progression is all about using chords in a major key that’s out of order.

It can start on any other key except for the I.

A key trait of many minor progressions is their tendency to go to major chords for stability.

This means that our ears want to go to musical places that are more pleasant to our ears.

If we kept going to other minor chords, the progression may feel weak and unstable and without a key center.

This is a big problem with composing in minor keys, but this progression is an example of how to rectify that problem.

i – III – VII – v

While the last example was a modal progression, this one is not for various reasons.

This is because all the chords exist perfectly in the key of A minor.

The example before had an F#, which was used in D major and was not a part of A minor.

Let’s break it down again for clarity:

- A Minor Scale = A – B – C – D – E – F – G

- Am (i) = A – C – E

- C (III) = C – E – G

- G (VII) = G – B – D

- Em (v) = E – B – D

Like the previous progression as well, it wants to use and go to stable harmonies like the III and VII chords.

It doesn’t return to a minor chord until the last bar.

Basically, it’s a good idea when using the minor key for composition to use a good mixture of major and minor chords.

One problem that many songwriters will encounter when using the III chord and the V and VII chords together is that they may not create a strong contrast between each other.

This is because Am and C, as well as G and Em, contain many of the same notes.

In this case, it works well because the tab of the arpeggiated riff has a similar pattern throughout the riff.

So to the listener, the Am to C transitions nicely into each other.

I – (III – IV) – V – (I – I7) – (IV – V)

I really wanted to include this example because it’s not a typical 12-bar blues progression, and its harmony suggests darkness though it’s set in a major key.

The progression does this by making the chords more ambiguous.

That means they’re not clearly minor or major, except for the I7 and the first G chord.

Nearly every other chord is played as a power chord.

This is a good trick with composing chord progressions if you do not like the mix of thirds and 7ths throughout it.

Another great trick to take away from this chord progression is making an I chord into a dominant 7th.

The I – IV chord change is used a lot in the blues and many genres.

So making the I chord a 7th chord helps increase its urgency to go to the IV chord.

The reason it wants to do this is that I is the relative V chord to IV.

The I-V chord change is the strongest chord change in western music, and lots of music is built around it.

Introducing a “relative V” chord helps mimic this sound and this tendency.

A quick breakdown can help you understand this if we were to treat C as the I chord:

- G7 = G – B – D – F

- C = C – E – G

- C major = C – D – E – F – G – A – B

- G major = G – A – B – C – D – E – F#

- D7 (V in G) = D – F# – A

I – vi – bVII – I

This is another example that uses the major key to sound minor, and it does this by using a different method than before.

So in the tab, we only have the full chords and not the actual riff.

The actual riff breaks apart these chords into arpeggiations, and the change from A to F#m sounds seamless because of that.

But that’s also because A and F#m have two of the same notes, like i and III or VII and v do in minor:

- A = A – C# – E

- F#m = F# – A – C#

- A major scale = A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G#

- A minor scale = A – B – C – D – E – F – G

- G (bVII in A major) = G – B – D

The other thing that this progression does is “borrow” a chord from A minor’s parallel scale.

G major is a bVII because the G# has been flattened to G.

The chord change of i – VII is used in many minor chord progressions and rock riffs, and this progression shows how easily you can start using this musical idea.

Although major and minor scales are extensively useful, they are not set in stone.

You can use some of the notes of these keys combined with notes “outside” of the key to getting really amazing progressions.

i – V7 – VII – IV7 – VI – III – iv7 – v7

This extremely famous chord progression comes from the great Eagles’ song “Hotel California.”

What’s important to notice about this chord progression is that the chords, once again, don’t stick to their key.

F#7 and E7/G# don’t appear in the key of B minor and function as a V7 chord and an IV7 chord, respectively.

Making a major chord out of the v and iv in minor is a very typical move and a necessary one sometimes if you want to avoid using the III, VII, and VI so much.

Take a look at the B minor scale and the chord breakdowns to see what I’m talking about:

- B minor scale = B – C# – D – E – F# – G – A

- Bm (i) = B – D – F#

- F#7 (V7) = F# – A# – C# – E

- Asus2 (VII) = A – E – A – B

- E7/G# (IV7) = E – G# – B – D

- G (VI) = G – B – D

- D (III) = D – F# – A

- Em7 (iv7) = E – G – B – D

Learning how keys, chords, and scales work is the best way to understand progressions like these.

It’s the way we’re able to reveal this information to you and help you see ways to use the minor key as these great songwriters do.

i – VII – VI – VII

This is another great but often-used chord progression in minor keys.

It takes advantage of some of the strongest harmonies available from the key’s seven notes and gives an epic feel that’s routinely taken advantage of.

If you were able to follow the discussion up to now, you should be able to see and know how the chords above go together, but we’ll break this down too:

- C# minor (E major relative minor) = C# – D# – E – F# – G# – A – B

- C#5 = C# – G#

- B5 = B – F#

- A5 = A – E

If you take away nothing else from this article, it should be that you can make a great chord progression in minor by just putting the i, VII, and VI chords together.

i – III – IV – VI – i – V – i – V

This classic song by The Animals may be one of the best minor progressions you’ll see in rock music.

It skillfully plays around with many of the harmonies available in A minor but moves the progression forward by going back to the i chord on the 5th bar.

I mentioned earlier that many minor chord progressions want to go to the III chord.

This is because the III chord is the I in the relative major, which in this case is C.

What we’re doing here basically is using a mode.

When using a mode, it’ll have the same chords as the major key it’s derived from but also want to end and begin on the relative I and V chords.

As usual, this is all easier when you break it down:

- A minor scale = A – B – C – D – E – F – G

- A harmonic minor = A – B – C – D – E – F – G#

- Am (i, vi in C major) = A – C – E

- C (III, I in C major) = C – E – G

- D (IV, II in C major) = D – F# – A (notice F# is not in the scale)

- F (VI, IV in C major) = F – A – C

- E (V, III in C major) = E – G# – B (G# is also not in the scale)

Another factor in minor chord progressions is using the major 7th interval (G# in this case of A minor) to create a harmonic minor scale.

Using this scale turns the v into a major V chord because the 7th scale degree is the 3rd of V.

Lots of nerdy theory stuff here!

Just look at the composition of everything above, and you’ll see that the E chord doesn’t have the G natural note.

i – III – VII – IV

This progression from Pantera’s classic “Cemetary Gates” uses several of the elements we’ve talked about already: going to the III, using the VII, and then turning the iv into a major IV chord.

There are some interesting things Dimebag Darrell did when writing this chord progression by making the III a sus2 chord and the IV a maj9 chord.

Now he may not have consciously chosen these intervals, but it shows some more cool things you can do with any minor key.

Adding a sus2 or sus4 interval is a great way to neutralize a chord’s major or minor sound.

For instance, using a sus2 on a minor chord and removing the third can make it sound major.

Then adding the maj7 (C#) and 9th (E) to D can make it sound a little minor but not as dark with that minor 3rd thrown in.

Basically, what I’m saying is these chords don’t have the third there, and that gives you more possibilities for molding the sound of the chord progression.

i – VII – IV7 – bII – III

This progression from Megadeth carries many of the same ideas using sus intervals and removing the thirds.

It also ends on a III chord.

What Dave Mustaine did here, though, is something used quite a bit in classical music.

By taking the ii chord in minor, which is usually diminished, and lowering the root by one-half step, you get a bII chord.

This chord is often used to go to the IV chord or back down to the i chord.

It’s just another major chord that you can throw into a minor key to get some interesting results.

Here’s a breakdown to help you see this idea:

- F# minor scale = F# – G# – A – B – C# – D – E

- F#m (i) = F# – A – C#

- Esus4add6 (VII) = E – C# (6th) – E – A (sus4)

- B7 (IV7) = B – D# – F# – A (no D# in F# minor)

- Gsus2 (bII) = G – B – D – A (no G in F# minor)

- A (III) = A – C# – E

i – iv – VII – (III – VII6)

This progression is a more straightforward minor chord progression that’s free of chromaticism or modal harmonic choices.

The most interesting part of this progression is how it raises slowly to the G chord.

This is done by harmonizing the open E note, F, and G note.

Careful attention to the top voices in a progression is the secret to writing better progressions and riffs.

Voice leading is the art of harmonizing the voices in the top voice or any other voice through a skillful choice of harmony.

It’s essentially what every songwriter does when they put chords together, but choosing the top voices just mentioned is a higher level than many are willing to go.

i – VII

This may be one of the most memorable progressions in this discussion, yet it only uses two chords.

It all goes back to knowing the minor key and choosing some of the most stable harmonies available, which is VII in this case.

However, this example is in a key not often used in guitar music, Ebm.

Gb is the relative major and has 6 flats in it.

There are lots of interesting sounds to be found in this key, but the amount of sharps makes it challenging to work through in a theoretical context.

I recommend studying the following breakdown, as usual:

- Eb minor scale = Eb – F – Gb – Ab – Bb – Cb – Db

- Ebsus2 (i) = Eb – Bb – Eb – F

- Gb (III) = Gb – Bb – Db

- Abm (iv) = Ab – Cb – Eb

- Bbm (v) = Bb – Db – F

- Cb (VI) = Cb – Eb – Gb

- Db (VII) = Db – F – Ab

(i – VII – VI) – III6 – VII

I like to see this chord progression from the famous Dire Straits song as a variation of the i – VII – VI progression we discussed earlier.

It’s a secret for many songwriters to take a well-known chord progression and throw in a few other chords or move them in various places in the measures to make it sound completely different.

Lots of music has used these three chords in the minor scale, just like tons of songs have used the I, IV, and V chords.

A lot of times, it just comes down to playing it in your own unique way.

i – (III – iv)

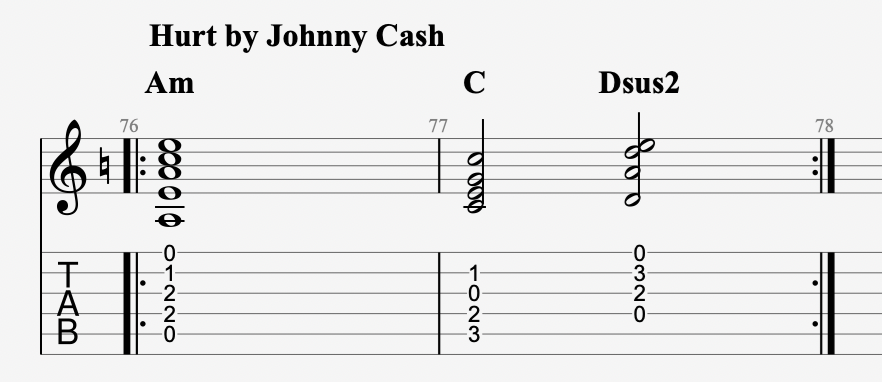

Depending on how you see it, this Nine Inch Nails or Johnny Cash song uses some of the ideas we’ve already covered.

The C is the III chord of A minor, and it’s thus not surprising to see it being used.

The Dsus2 is used in a way to suggest a major sound without using the third.

Otherwise, this would be a Dm chord if we were to stay strictly in the key of A minor.

As you can see, though, by now, it’s no fun to just sit in these 7 notes and not explore the possibilities of other sounds.

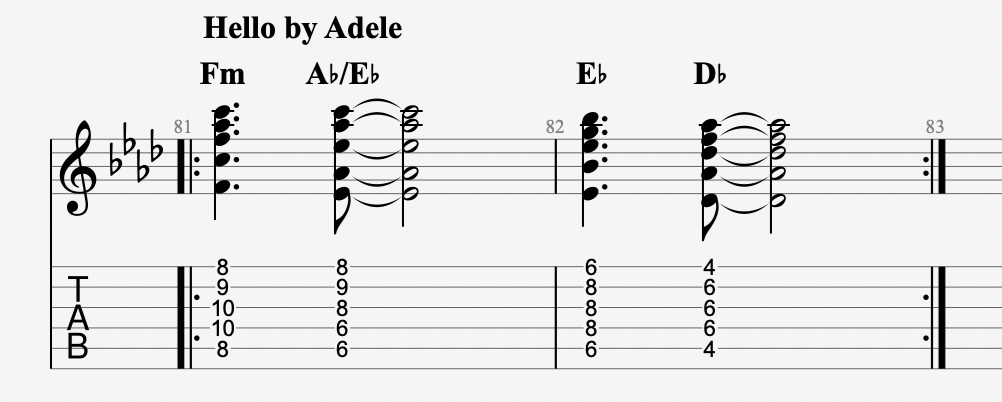

(i – III6) – (VII – VI)

The last song we’re going to cover brings us back to the key of F minor and oddly uses almost all the same chords as “Smells Like Teen Spirit”…..

Yep. This time the chord progression has no hint of power chords and instead uses a full-fledged voicing of each harmony with thirds and all.

It also has some carefully chosen voice leading by using only three notes in the top voice: C, Bb, and Ab.

Funny how often things reappear, right?

A brief look at the minor key

The minor key is not as straightforward to use as the major scale for various reasons.

First, the most stable chords to use in any minor key are VII, VI, and III.

Second, lots of progressions songwriters create will end up wanting to go to the III chord. Third, the iv and v are minor chords and, thus, don’t want to resolve as strongly back to the i chord.

Composers over the centuries have found many solutions to these problems, which mostly involve altering the 7 notes used in a minor scale to give them more chord options.

This is what’s often lost when talking about guitar music theory.

You are not bound to stay strictly within the natural minor or major scale.

Many of the progressions we’re about to discuss will show you what we’re talking about.

To make sure you’re ready to take in a lot of this information, here’s a breakdown of the E minor key, which is one of the most popular out there.

Use it as a reference for finding other keys’ respective VII, VI, and III chords.

- E minor scale = E – F# – G – A – B – C – D

- Em (i) = E – G – B

- F#m7b5 (ii7b5) = F# – A – C – E

- G (III) = G – B – D

- Am (iv) = A – C – E

- Bm (v) = B – D – F#

- C (VI) = C – E – G

- D (VII) = D – F# – A

What is the saddest key of all?

There isn’t any music theory behind describing what personally feels sad to certain people.

In other words, the answer to this question is very subjective and really comes down to the composition of the piece and the message that the songwriter is trying to share.

You can write a sad song from a key that sounds “happy,” and you can also write a happy song from a key that sounds “sad.”

However, for some reason, if you ask this question to multiple people or even search for its answer only, you’ll learn that:

Most musicians find the key of D minor as the saddest key.

The reason behind this is, again, subjective and general consensus.

Here are some common chord progressions in the key of D natural minor:

| i – iv – VII | Dm – Gm – C |

| i – iv – v | Dm – Gm – Am |

| i – VI – III – VII | Dm – Bb – F – C |

| i – VI – VII | Dm – Bb – C |

| i – iv – V – i | Dm – Gm – A – Dm |

| i – v – VI – VII | Dm – Am – Bb – C |

| i – III – VII – iv | Dm – F – C – Gm |

What makes a minor chord progression?

For a chord progression to be a minor chord progression, it must be composed of chords built upon the notes of a minor scale.

Generally, this means that at least one chord in the progression will have a root note based on the sixth degree of the scale (also known as the “submediant”).

This can include the minor i-IV-V, i-iv-VII, or other combinations of notes, along with variations within the progression.

The minor i-IV-V is often considered a basic chord progression, and it consists of three chords: the tonic (i), subdominant (IV), and dominant (V).

So, for example, if the root note is C, the progression would be Cm-F-G.

The minor i-iv-VII progression consists of three chords: tonic (i), submediant (iv), and leading tone (VII).

In other words, if the root note is D, the progression would be Dm-Gm-C7.

The beauty of minor chord progressions is that they can sound complex and interesting while still being relatively easy to play.

They are often used in blues, jazz, and rock music as a way to create tension and contrast.

These progressions also provide an opportunity for improvisers to explore differently-toned chords.

Overall, minor chord progressions offer musicians a way to add interest and complexity to their music without learning complicated chord shapes or voicings.

Differences between a minor and a major chord

A minor chord consists of a root note plus the notes that are three and four steps above it.

In other words, if we use C as our starting point, then a minor chord would be composed of C, E-flat, and G; while a major chord is constructed by adding a fourth step (in this example, A) to the major chord.

Minor chords are generally more melancholy and somber, while major chords have a brighter, happier sound.

Additionally, minor chords often use flatted (or lowered) third and fifth notes in the scale, while major chords use natural (or regular) third and fifth notes.

This changing of tones gives each type of chord its character and sound.

Finally, it’s important to remember that minor chords don’t always have to be depressing or sorrowful; they can also create a gentle, soothing atmosphere.

Minor chords are often used in classical pieces as well as romantic songs.

Ultimately, both types of chords can be used to create unique and exciting sounds and emotions.

All that matters is how you use them and the context of your music.

Loves studying classical piano, youtube video tabs, and music theory textbooks to get insights into guitar playing that no one else has uncovered yet. In his spare time, he can be found relaxing at the beach in San Diego, or adventuring somewhere around the world.